Click List of Articles here to see the complete list.

A little background

I’ve been writing articles on a variety of people and topics since the mid-1980s. Most focus on subjects that interest me. Nothing has changed, and I will continue to write about people who interest me.

— Ned Wynkoop I created this image of Ned Wynkoop (above, © Louis Kraft 2013) for the August 2014 issue of Wild West magazine (“Wynkoop’s Gamble to End War”). Also, I wasn’t thrilled with it (perhaps because the art director insisted on over two pages with a terrible cropping), and repainted it for in Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020).

I created this image of Ned Wynkoop (above, © Louis Kraft 2013) for the August 2014 issue of Wild West magazine (“Wynkoop’s Gamble to End War”). Also, I wasn’t thrilled with it (perhaps because the art director insisted on over two pages with a terrible cropping), and repainted it for in Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (University of Oklahoma Press, 2020).

— Cheyenne Indians

— Black Kettle

— Sand Creek Massacre

— George Armstrong Custer

— Arapaho Indians

— Little Raven

— Kit Carson

— Errol Flynn

— Olivia de Havilland

— Charles Gatewood

— Apache Indians

— Geronimo

Left is a copyrighted portrait of Geronimo (above) that I created in March 2015. Although the Wild West staff liked it, the Los Angeles designer for the World History Group (which purchased the Weider History Group in spring 2015) did not, and it wasn’t used with my cover story for the October 2015 issue of Wild West entitled “Geronimo’s Gunfighter Attitude.”

Left is a copyrighted portrait of Geronimo (above) that I created in March 2015. Although the Wild West staff liked it, the Los Angeles designer for the World History Group (which purchased the Weider History Group in spring 2015) did not, and it wasn’t used with my cover story for the October 2015 issue of Wild West entitled “Geronimo’s Gunfighter Attitude.”

Below is the cover for the October 2015 Wild West article.

This is the second time that Wild West has printed one of my Apache stories with the same Howard Terpning painting of Geronimo on the cover. The first was for the October 1999 issue of Wild West for an article titled “Assignment: Geronimo” (see banner above).

Long time gone

Back in 2015 I was forced to quit doing talks and writing articles due to a lot of reasons, two of which have been an overload of work and ongoing deadlines (among other nasty things). Thanks to True West editor Stuart Rosebrook, this self-proclaimed vanishment came to an end. As of late 2019 I began to write for for magazines again. My first feature was in the February-March issue of True West Magazine.

The article features Black Kettle, and is titled “Black Kettle: The People’s Peacemaker.” The Cheyenne chief, along with Arapaho Chief Little Raven, are the two leading American Indians in my upcoming book, Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (University of Oklahoma Press, available on March 12, 2020).

The article features Black Kettle, and is titled “Black Kettle: The People’s Peacemaker.” The Cheyenne chief, along with Arapaho Chief Little Raven, are the two leading American Indians in my upcoming book, Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (University of Oklahoma Press, available on March 12, 2020).

I thought that I knew a lot about both of these extraordinary men when I began the project. Not close; I can’t tell you how much I have learned about them during the research and writing of the Sand Creek story. They aren’t as they have often been portrayed. Why? My best guess: a lack of research by lazy writers who copy what is already in print without confirming the supposed facts that they use.

To see most of the article, click Black Kettle: The People’s Peacemaker.

Shockingly two images in the True West Feb-Mar 2020 article were left out of the online posting of it. The question is why? Four portraits that are small and appear at the top of p31 in the magazine are now huge in the above link (Wynkoop, Hazen, Custer, and Sheridan). Again why? Wynkoop appears at different times in the story and knew Black Kettle well; Hazen is important for he sealed the chief’s fate. Perhaps these four images should have been reduced in size and placed near where they appeared in the story.

Only two confirmed images of Black Kettle exist, and both were created by Wynkoop’s father-in-law George Wakely after the Camp Weld council with Territorial Colorado governor John Evans on September 28, 1864, ended (see above photo; p32 in article). The article is about Black Kettle, but for some unknown reason the group shot with him an others was deleted, and of all the images in the online posting only a detail of Black Kettle pulling Medicine Woman Later onto his from Steven Lang’s huge mural of the Battle of the Washita was used in the online posting. … Although I had suggested Lang’s detail, perhaps I should have suggested one of my portraits of Black Kettle.

Only two confirmed images of Black Kettle exist, and both were created by Wynkoop’s father-in-law George Wakely after the Camp Weld council with Territorial Colorado governor John Evans on September 28, 1864, ended (see above photo; p32 in article). The article is about Black Kettle, but for some unknown reason the group shot with him an others was deleted, and of all the images in the online posting only a detail of Black Kettle pulling Medicine Woman Later onto his from Steven Lang’s huge mural of the Battle of the Washita was used in the online posting. … Although I had suggested Lang’s detail, perhaps I should have suggested one of my portraits of Black Kettle.

Ditto a fantastical British illustration by an artist that had no clue of what Black Kettle, John S. Smith, or Ned Wynkoop looked like, much less of how they would have been attired. I had purchased this image for possible inclusion in Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek (University of Oklahoma Press, 2011), but decided against using it, as I didn’t want to waste words discussing how inaccurate the art was. … I again considered it for Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (University of Oklahoma Press, March 2020), but again quickly dismissed the idea.

When I saw the first True West proof of my story, and it included the above image (p33 in the article), I was thrilled, but knew that some of the errors in it needed to be explained. I shared some of this information with editor Stuart Rosebrook, and he changed the caption. Finally my gutless shying away from using the art in my books would now see the light of day in one of my articles. Thanks Stuart!

When I saw the first True West proof of my story, and it included the above image (p33 in the article), I was thrilled, but knew that some of the errors in it needed to be explained. I shared some of this information with editor Stuart Rosebrook, and he changed the caption. Finally my gutless shying away from using the art in my books would now see the light of day in one of my articles. Thanks Stuart!

The times have changed

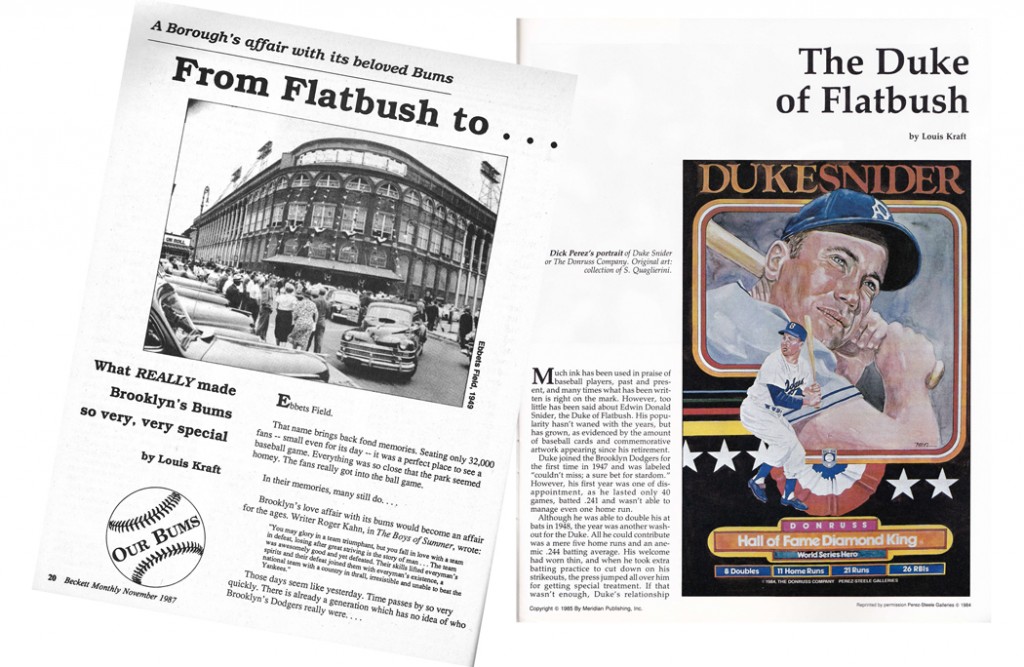

Early during my writing life I wrote about baseball, including Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in 1947, along with Duke Snider, another rookie that year, in “From Brooklyn to … our fondest memories” (see image, below). Part of the story went: “It was [Dodgers general manager Branch] Rickey and Robinson vs. the Dodgers. At the outset, returning veteran and Kentuckian Pee Wee Reese told Rickey: ‘My grandfather would turn over in his grave if he knew I was playing on a team with a colored boy.’ The shortstop asked to be traded. Supposedly others signed a petition refusing to play with Robinson. Rookie Duke Snider wouldn’t sign the petition. Others followed his lead and the team split. … One incident signifies this merging of white and black as a working unit.” … Early that season “racial tensions [in Cincinnati, Ohio] permeated the ballpark.” When the Dodgers took the field in the first inning, Reese walked over to Robinson and placed his right arm over his shoulder. The Cincinnati stadium turned silent—deadly silent. “At this late date [1987] in time no one is quite sure if the incident is legend or reality, … but “[t]hat 1947 season was special … ” and so were the following years that eventually resulted in Brooklyn’s first and only World Series victory (1955).

“From Flatbush to … our fondest memories” (Beckett Monthly, November 1987; the title spread over two pages), which featured Robinson, Reese, and Snider; and “The Duke of Flatbush” (Sports Parade and Sports North, both published in 1985). I spent time with Duke Snider on three or four occasions at this time and pitched him on partnering to write his biography (but was too late for the Duke had already signed a contract to work with Bill Gilbert, with the resulting book being The Duke of Flatbush, 1988).

Baseball writing continued with Philadelphia Phillies great Mike Schmidt and Bill Buckner, a Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder who could no longer play the outfield because of an injury. Buckner, who also played for the Cubs, Red Sox, Angels, and Kansas City, became my main subject because of his all-out effort. He was a terrific player, but when considered he played most of his career on a damaged ankle that impacted his walking and running, his achievements on the field were extraordinary. In 1988 an interview I did with him was published (I landed the interview mainly because of an article I had written about him in the May 1985 issue of Baseball Digest (a cool magazine that no longer exists) and a couple of early Wynkoop articles that he liked). The following image contains the first two pages from the interview. Marcia Greenwood, a baseball connection of mine in Boston, took this photo of him for me to submit with the interview.

After Buckner’s error in the 1886 World Series (which didn’t lose the fall classic even though he has since shouldered the blame), I pitched Playboy on doing an interview on him, beginning the query with: “Bill Buckner attempted to commit suicide last week. He jumped in front of a truck, but it went right through his legs.” The editor loved the query, but declined the offer as he didn’t think Buckner would be an interviewee that all his readers would recognize. It hurt to lose the sale (it would have been a great interview), but the kind words eased the loss of $10,000 (the pay for an interview at that time). Perhaps I’ll return to Buckner someday, for there’s more to explore here.

The writing began to change. There were some Indian wars articles, … but in 1990 I wrote about pirate Henry Morgan and Buffalo Bill Cody for the Lincoln Homework Encyclopedia. When I pitched the encyclopedia to write the article on Jackie Robinson it was accepted. However, when I submitted the finished piece, all hell broke loose. At this point in time, this encyclopedia (and others) printed white-washed propaganda about Robinson’s breaking of baseball’s color line. Pure bullshit and inaccurate. My article corrected the fiction and detailed what Robinson really went through on and off the baseball field.

During the 1960s I had marched in support of Martin Luther King, Jr. This wasn’t an arbitrary choice. My parents were unprejudiced (although strangely my sister and brother harbored prejudices). With my mother and father’s influence strongly imbedded in me, in 1970 I joined VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), hopping to work with American Indians. But fate intervened during the wee hours one night in Austin, Texas (where I trained). Let’s just say that when a knife is at your throat that words come trippingly off the tongue. The next morning I was a celebrity. Hogwash! I was little more than a frightened person who was thrilled to see a new day. No Indians for Kraft. I would live with and work with African Americans in Oklahoma City. Although my views on race were already in place, this period of my life confirmed who I was and where I stood.

Lee Kraft (October 1, 1956–March 6, 1990). His image belongs here for his death impacted the direction of my life and writing. (Photo © Louis Kraft 1989)

The encyclopedia editor assigned to me called and attacked the Jackie Robinson story with guns blazing. Using a voice of condensation that I can still hear, he stated that under no circumstances would they print my inflammatory crap and that I needed to rewrite the story to reflect what was already in print. I told him that I wouldn’t do this. “You will do as told,” he screamed into my ear. “No, I won’t, for I quit,” I said and hung up the phone. A month or two passed and another editor called me. After saying that my former editor had been fired, he asked me to continue writing for the encyclopedia. I asked about the Jackie Robinson piece. After he said that it had been reassigned, I told him I appreciated the offer but would pass. No more encyclopedia writing for me.

The year 1990 proved to be a year I would never forget. In January I had a knee operation, the first of 11 or 12 operations—I’ve lost count. In March I began writing for a software company. That same March my brother, who I was close to, worked with, partied with, and played softball with (for the last 10 years), died in a horrific car wreck. This is still the most shocking event in my life, and combined with the encyclopedia fiasco marked the end of my relationship with baseball, for after the publication of “Baseball on the Frontier” (winter 1990), I never wrote about it, played on a team, or followed the sport again. I quit cold turkey, just like quitting cigarettes (and I didn’t gain any weight).

My first Indian wars sale (of course a “pay on publication” contract) was a full-length feature on George Armstrong Custer for a British history magazine in the early 1980s. I waited and waited, but the issue with the article never materialized even though I was constantly told the “next” issue. Eventually the magazine disappeared from California newsstands. Nervous, I wrote the editor. He received it at his residence and wrote back that the magazine no longer existed.

End of story? Not quite. I wrote back, asking that he return all of the photos of Custer that I had submitted to accompany the article. The editor was honest and returned the photos. The article eventually saw print in a journal four years later.

Since then Mr. Custer has been very good to me, appearing in numerous articles. One of them, “Custer, the Little Bighorn & History” first appeared in the June 2006 issue of American History magazine and continues to be available online as “George Armstrong Custer: Changing Views of an American Legend” thanks to Weider History Group.

Charles Gatewood. Geronimo. Apaches. I knew nothing about them and didn’t care. In 1993 I saw Geronimo: An American Legend. Liked the scope, but not the film as it had no focus. Two and a half years later while signing Custer and the Cheyenne in Scottsdale, Az., I heard of the Gatewood Collection in Tucson, and the following month spent a week looking at it. Wow! An eye opener! Wynkoop was supposed to be the next book. Didn’t happen. Gatewood, Geronimo, and the Apaches dominated my next 10 years. Good years. As the Gatewood character in Geronimo: An American Legend says, “The Apaches are special.”

My favorite article dealing with Mr. G & Mr. G is “Assignment Geronimo” (Wild West magazine, October 1999, … see the Articles tab, above, for the cover). Since then it has been available on the web under the title “General Miles and the Expedition to Capture Geronimo,” again thanks to the Weider History Group.

Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland joined my writing life while I was walking with G&G. They had both been with me since I was a boy, and never left. But it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that I decided to write about them. Like Indian wars research, the deeper I dig into their lives the more I realize that what I thought I knew isn’t true. I’m not blaming memoirs, for often (as I learned while researching the Indian wars) they are often based on memory. Mine has certainly changed over the years, as had theirs … and yours. Unfortunately much that is written by so-called historians is based upon books and articles by secondary sources for these are easy to find whereas primary sources are often much harder (and more costly) to find. There is an adage: “If it is in print, it must be true.” Yeah, … right. None of the Flynn or Flynn/de Havilland articles live on the internet (at least not that I’m aware of). My favorite was printed in American History (February 2008) and was titled “Custer: The Truth Behind the Silver Screen Myth.” Although American History sold Custer (see the American History image on the Articles tab, above), the lead in the article is Flynn, and this article is by far the best of my Flynn-Custer articles.

My first published article on Wynkoop appeared in 1987, and the following year my first article on him appeared in a national magazine. It was a story of peace, but the publication changed my title to: “Shoot Them On Sight.” When I heard that they intended to reprint the article in another national magazine, I asked that they change the title (and submitted a list of suggestions). They changed the title, to “The Order: ‘Shoot Them On Sight.’” All said and done, that magazine and its sister publications are a class act and I’ve been fortunate to have a good relationship with them over the years.

Ned Wynkoop started fast in my articles life, slowed to a crawl, then surged forward. Currently 14 articles have appeared in magazines and anthologies. Two additional articles will see print in Wild West magazine, and another feature is almost ready for delivery.

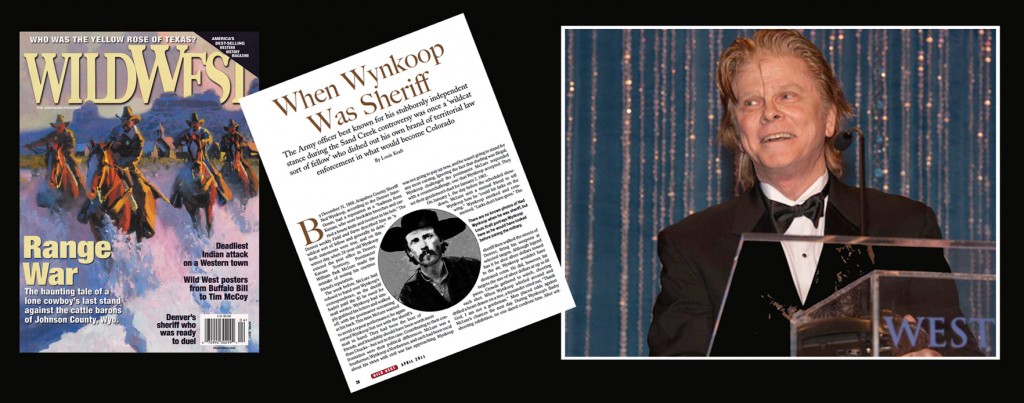

“Ned Wynkoop & Black Kettle” (Research Review, June 1995) won the Dr. Lawrence A. Frost Literary Award in 1996, and in 2012 “When Wynkoop Was Sheriff” (Wild West, April 2011) won the Western Heritage Wrangler Award.

“When Wynkoop Was Sheriff”

Acceptance Talk for the Wrangler Award in OK City (April 21, 2012)

As the days move forward more articles will continue to be written dealing with the Indian wars and the Golden Age of Cinema.

| Louis Kraft writer © Louis Kraft 2013–2024 |