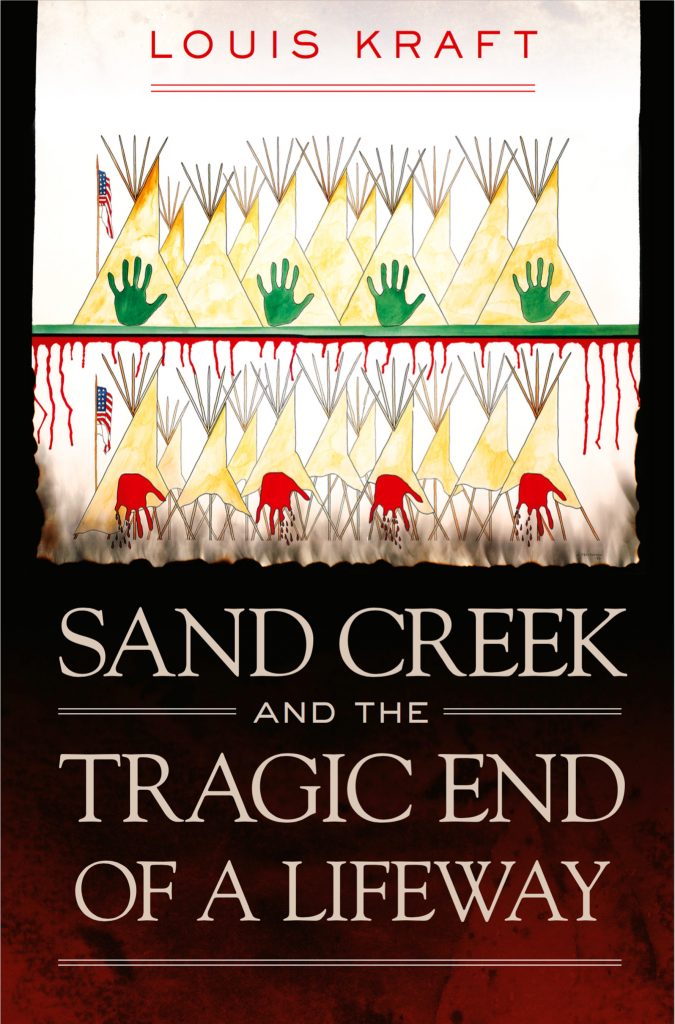

University of Oklahoma Press (2020)

Eighteen-sixties Colorado Territory. Cultures in conflict.

This is a story of people, expansion, conquest, fear, love, survival.

It is a story of people carving out a new world. It is a story of people

struggling to preserve their religion, language, land, freedom, and

lifeway. It is a story of people caught between two worlds.

Finally it is a story of people who challenged their world

It is a story of life, and ultimately disaster. It is a story

that is as alive today as it was in the 1860s.

This isn’t a story of villains or victims; rather it is a story of people.

A story that will live for all time.

There are two major updates for

Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway

- The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum awarded it the Wrangler for best nonfiction book of 2020.

- The Colorado Authors League also named it best nonfiction book for 2020.

The book won the award for the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum Award for best nonfiction book of 2020. My point of view: Wow! This is the most important award I’ll ever win as an Indian wars historian.

I won a Wrangler Award in 2012 for an article of mine, “When Wynkoop was Sheriff” (Wild West magazine, April 2011). As I haven’t posted many images of the 18-pound Wrangler Award of a cowboy on a horse I took a photo of me holding it on June 6, 2021. It is to the right.

I won a Wrangler Award in 2012 for an article of mine, “When Wynkoop was Sheriff” (Wild West magazine, April 2011). As I haven’t posted many images of the 18-pound Wrangler Award of a cowboy on a horse I took a photo of me holding it on June 6, 2021. It is to the right.

I’m excited, and so is Pailin, for the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum Wrangler Awards weekend is on par with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences Oscar award ceremony at the beginning of each year.

This is not an understatement. More, Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway is a finalist in the Colorado Authors League awards for 2020 as the best nonfiction book of 2020. It’s a cool organization and I’m thrilled. I created a short video that they requested that I record for them. Unfortunately I haven’t figured out to how to place it here.

Short LK talk for the Colorado Authors League

It is on YouTube:

LK talks about the writing of Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway for CAL

Available from

University of Oklahoma Press

Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Goodreads

From the dust jacket

Nothing can change the terrible facts of the Sand Creek Massacre. The human toll of this horrific event and the ensuing loss of a way of life have never been fully recounted until now. In Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway Louis Kraft draws on the words and actions of those who participated in the events at this critical time.

The history that culminated in the end of a lifeway begins with the arrival of Algonquin-speaking peoples in North America, proceeds through the emergence of the Cheyennes and Arapahos on the Central Plains, and the incursion of white people with a lust for land and gold. Beginning in the earliest days of the Southern Cheyennes, Kraft brings the voices of the past to bear on the events leading to the brutal murder of people and its disastrous aftermath. Through their testimony and their deeds as reported by contemporaries, major and supporting players give us a broad and nuanced view of the discovery of gold on Cheyenne and Arapaho land in the 1850s, followed by the land theft condoned by the U.S. government. The peace treaties and perfidy, the unfolding massacre and the investigations that followed, the devastating end of the Indians’ already circumscribed freedom—all are revealed through the eyes of government officials, newspapers, and the military; Cheyennes and Arapahos who sought peace with or who fought Anglo-Americans; whites and Indians who intermarried and their offspring; and whites who dared to question what they considered heinous actions.

The history that culminated in the end of a lifeway begins with the arrival of Algonquin-speaking peoples in North America, proceeds through the emergence of the Cheyennes and Arapahos on the Central Plains, and the incursion of white people with a lust for land and gold. Beginning in the earliest days of the Southern Cheyennes, Kraft brings the voices of the past to bear on the events leading to the brutal murder of people and its disastrous aftermath. Through their testimony and their deeds as reported by contemporaries, major and supporting players give us a broad and nuanced view of the discovery of gold on Cheyenne and Arapaho land in the 1850s, followed by the land theft condoned by the U.S. government. The peace treaties and perfidy, the unfolding massacre and the investigations that followed, the devastating end of the Indians’ already circumscribed freedom—all are revealed through the eyes of government officials, newspapers, and the military; Cheyennes and Arapahos who sought peace with or who fought Anglo-Americans; whites and Indians who intermarried and their offspring; and whites who dared to question what they considered heinous actions.

As instructive as it is harrowing, the history recounted here lives on in the telling, along with a way of life destroyed in all but cultural memory. To that memory this book gives eloquent, resonating voice.

As Kraft received his second National Cowboy & Western Heritage Award for this book, and as the review section is lengthy, I’ve added some of the images from the awards weekend in Oklahoma City to the following reviews.

Reviews

“What happened was inevitable. The way it happened was unconscionable.”

“Opening my review with the last two sentences of this book, a quote from a movie no less, seemed a little trite to me at first, but I kept coming back to this powerful ending to Louis Kraft’s long awaited comprehensive examination of one of the most tragic and perplexing events in the history of the American West. Until now, small portions of the complicated history of the Sand Creek Massacre were scattered across dozens of books, biographies, autobiographies, Native American storytelling, letters, dissertations, documentaries, personal papers, and endless reams of government documents. In fact, the horrid details of the 1864 massacre in Colorado didn’t fully impact the general public until two letters written by participants were discovered and printed in Denver’s Rocky Mountain News in 2000, more than 130 years after it happened. Perhaps this is why it took so long for a historian the caliber of Kraft to gather and unpack the capacious details, dispel many incorrect assumptions, and concisely set the record straight.

After I received the Wrangler for Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway on 17sept2021 I refused to leave it with the lady who helped me off the stage. Instead I walked to our table at the rear of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage banquet hall and asked Pailin to pose for a few photos of us with our cowboy. When the awards ceremony ended I returned the 20 lb. Wrangler bronze to the lady working stage left to mail it to us. (photo © Louis Kraft & Pailin Subanna Kraft 2021)

“Who better to undertake this titanic task than the biographer of Major Edward Wynkoop, a key player in the event? Louis Kraft’s thorough look into the life of the venerable Wynkoop set the stage for this Sand Creek book, for with the exception of the architect of the massacre, John M. Chivington, no single participant stood at the center of the controversy more prominently than Wynkoop. If not for his bold and often clumsy penchant for confounding and sometimes flat-out defying his commanders, one wonders if Wynkoop might have intervened and stopped Chivington – or died trying.

“Stan Hoig gave us a blueprint of the Sand Creek Massacre in his well-regarded 1960s book, but Kraft’s work carefully constructs the entire story and fills many significant voids Hoig only casually outlined. Kraft correctly traces the massacre to the early 1800s, when the Louisiana Purchase opened the gates to burgeoning anglo western expansion in the 1850s, when all bets for peaceful relations between whites and Indians were off due to the discovery of gold and the emerging and ultimately catastrophic American Civil War. More interestingly, Kraft delves deeply into Cheyenne and Arapaho origins, which is significant to understanding how and why they were set on a collision course with the emigrants from the new world.

“I’ve long admired Kraft’s work not only for his attention to detail, but also for his obvious passion for his subject matter, something often lacking in a non-fiction historical work such as this. The book is meticulously annotated, with detailed footnotes in which Kraft compares and contrasts past inconsistencies or errors made by his predecessors with solid research gleaned from the formidable stack of sources spanning the past century. The last few decades ushered in a revival of interest in the Sand Creek Massacre since Hoig’s work, thanks to new writers, biographers, and historians who’ve presented dissenting opinions, stimulated new research, and given life to the names of Chivington, Wynkoop, Soule, Smith, Bent, Evans, Black Kettle, Bull Bear, and Left Hand. For my money, any serious research into the Sand Creek Massacre must now begin with this excellent book.”

— Kevin Cahill, author of Sand Creek, an historical novel (Lone Wolf, 2005) and administrator an in-depth website on The Sand Creek Massacre

Cahill’s Amazon review (July 3, 2020)

“Louis Kraft’s comprehensive work is a welcome addition to the canon on the Sand Creek Massacre.* Building on his earlier biography of Edward ‘Ned’ Wynkoop, one of the principal actors in attempting to prevent the tragedy, Kraft adds much-needed context, stretching from the first Cheyenne (or, more accurately, Tsistsista) incursions onto the Central Plains through the tragic confinement on ill-suited reservations in present-day Oklahoma. As Kraft’s title suggests, his work is not a narrative of ‘extermination’ or ‘removal,’ as both northern and southern bands of the people still maintain vibrant communities in the region today, but rather an end to the nomadic lifestyle that has become the archetype of the American Indian. Kraft traces from multiple perspectives, in a style reflective of other recent works on the Plains, the various actors and events that led to the Sand Creek Massacre, though the approach is sometimes disjointed, resulting in a ‘stream of consciousness’ narrative. He spends a lengthy conclusion explaining how that event shaped subsequent treaties and helped the settler colonists prevail in their efforts to re-people the Plains.

“Kraft’s work is deeply researched, uncovering virtually every shred of surviving evidence

related to the massacre and its participants and victims. But he does not rely exclusively on the documentary record, which often skews the narrative towards the Anglo version of events. He takes great care to privilege Tsistsista and Hinono’eino (Arapaho) sources and views, though an assessment of his success in doing so is better left to those more qualified to judge. The work traces how each side struggled to make sense of its contact with the other, predictably breaking into ‘war’ and ‘peace’ factions on both sides. While government agents and traders, such as the famed William Bent, sought accommodation and understanding, other whites more intent on dispossession, removal, and extermination found ready accomplices in Col. John Chivington and Colorado’s territorial governor, John Evans, who both undercut efforts by Wynkoop, Silas Soule, and others more peaceably inclined to prevent the massacre. Similarly, tribal leaders such as Black Kettle and Little Raven sought accommodation while more warlike factions, such as the Dog Men, embarked on a more confrontational course. Predictably, Mars was ascendant, and the war factions on both sides temporarily gained the upper hand, with tragic results.

LK’s two Western Heritage Wrangler Awards. The one for “When Wynkoop was Sheriff” (Wild West magazine, April 2011 issue) is in the background and the one for my 2020 book Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway is in the foreground. LK’s 1970 ink art of Ned Wynkoop is at left and a photo of Ned Wynkoop that is on my Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek (2011) book cover is on the right. (Photo © Louis Kraft 2023)

“But throughout the narrative, Kraft emphasizes agency on both sides, most notably through the actions and conversion of Wynkoop, who makes the transition from Indian hater to cautious intermediary to agent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, before resigning in disgust with the government’s duplicity. But Wynkoop’s path suggests there was another way, that conflict was not inevitable, though there are always men such as William Byers, editor of the Rocky Mountain News, who goaded political and military leaders into action by inflaming his readership. Similarly, Black Kettle’s attempts to reach accommodations with whites led only to his presence at two of the most notorious episodes on the Central Plains, Sand Creek and the Washita Massacre in 1868, which finally cost him his life. While Kraft’s argument, that the established Native American lifeway on the Central Plains ended through the concerted efforts of white settlers, is clearly proven, the hidden subtext is that there might have been another path, had both sides been able to commit to it. And that, in the end, is perhaps the work’s most enduring legacy—that conflict was and is not inevitable, and that there are always those on both sides who are eager to serve as peacemakers, though their efforts are not often rewarded.”

— Christopher M. Rein, Air University Press, Pelham, AL

Nebraska History (Winter 2020)

“Louis Kraft has written many articles for Wild West and other publications, as well as seven books, including the 2011 biography Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road From Sand Creek. One of his favorite figures on the Western frontier remains Wynkoop, the Army officer who among other things tried to bring about peace before the Nov. 29, 1864, tragedy in Colorado Territory known as the Sand Creek massacre. Wynkoop receives plenty more attention in Kraft’s most ambitious work to date, but the focus of this well-researched book is on the destruction of the way of life of the Cheyennes (Tsistsistas) and Arapahos (Hinono’eino), who took a major hit when Colonel John Chivington attacked and destroyed the village of Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle at Sand Creek. Though Chivington called the engagement a battle, he resigned from the Army three months later and was condemned for what one Army judge called ‘a cowardly and cold-blooded slaughter.’

The four-day Wrangler Awards event that began for me and my absolutely beautiful wife Pailin (who is always gorgeous regardless of what time it is) on Thursday, 15sept2021, when we reported for a rehearsal wherein I became familiar with the podium and microphone while rehearsing what I would say on the seventeenth so that the camera crew knew what was coming. This image was taken while we walked on the red carpet for the second banquet on the evening of 18jun2021. (photo © Louis Kraft & Pailin Subanna Kraft 2021)

“Black Kettle, a chief who wanted peace, survived Sand Creek but was killed when Lt. Col. George Custer attacked his village on the Washita in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) on Nov. 27, 1868. In the aftermath Custer managed to avoid further bloodshed when he held back his soldiers and convinced Cheyenne Chief Stone Forehead to surrender after a dramatic standoff (detailed in Kraft’s October 1998 Wild West article ‘Confrontation on the Sweetwater’).* ‘More likely his decision not to attack—his shining moment on the plains—mimicked Chivington’s,’ Kraft notes, ‘in that he held the power to release two armies on a people, two armies that craved blood, but chose not to butcher children, women and men.’ There was more fighting up north, but Chief Tall Bull was killed at Summit Springs in July 1869, and the next month the Southern Cheyennes and Southern Arapahos were settled on the reservation at El Reno in Indian Territory. ‘Only a few Southern Tsitsista and Hinono’eino leaders survived the deliberate destruction of their people’s freedom and were herded onto their reservation in Indian Territory that none of them wanted,’ the author writes. ‘In a little more than two decades these once-proud people—the rulers of the central plains—had lost everything and had been reduced to paupers and prisoners in a foreign land.’

“Among the characters in Kraft’s well-crafted history are the prominent Indian leaders Black Kettle, Stone Forehead, Tall Bull, Bull Bear, Little Raven and Little Robe, as well as such mixed-bloods as the sons of William Bent and Edmund Guerrier. The author does not neglect the whites involved in this often-sad story. Colorado Territory Governor John Evans, who took a harsh stance against the Indians he thought were threatening Denver, comes across as misguided but not as bad as sometimes portrayed. Rocky Mountain News editor William Byers, a staunch defender of the anti-Indian vision of Chivington and Evans, might be considered a ‘villain’ in Kraft’s narrative, which is far more than simply another retelling of the horrific tragedy at Sand Creek.”

— Gregory Lalire, editor of Wild West magazine

HistoryNet (October 2020)

* Actually Custer’s meeting with Stone Forehead on the Staked Plains of Texas in March 1869 was the focus of Kraft’s book, Custer and the Cheyenne: George Armstrong Custer’s Winter Campaign on the Southern Plains (Upton and Sons, 1995).

“Veteran historian Louis Kraft, author of Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek, a 2012 Spur finalist, has dedicated much of his career to researching the incomprehensible massacre of a peaceful Cheyenne village in southeastern Colorado in 1864. Finally, his history of the massacre itself has been published. Kraft’s book is easily the most thorough and best written account of a repulsive act that still hurts and sicken Americans of all races more than 150 years later. Kraft chronicles the events leading up to the massacre, the horrific attack, and the aftermath. ‘I Stand by Sand Creek,’ the leader of the massacre, John Chivington, once said. Few stand by it today.”

— Johnny D. Boggs, Roundup Magazine (October 2020)

In his book Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway, Louis Kraft recounts the history surrounding the 1864 attack of an encampment of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapahoe by the Third Colorado Cavalry. The unrestrained acts of barbarism perpetrated by those under the command of Col. John M. Chivington is made all the more reprehensible by the fact that the Cheyenne leader Black Kettle assured the camp’s terrified inhabitants they were under the protection of the United States. The massacre still has significant reverberations within the Cheyenne and Arapahoe communities to this very day and remains a black eye on America’s national memory.

After the 17sept2021 luncheon banquet at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum where LK accepted his 2nd Wrangler award and Pailin and he met with people and then returned to her 2020 M-B CLA 250 to make a quick change to transform ourselves from a spiffily dressed award show couple into two westerners for the evenings’ festivities. (photo © Louis Kraft & Pailin Subanna Kraft 2021)

Kraft’s extensive writing concerning the time period and the area surrounding Sand Creek make this latest endeavor seem long overdue. In it, he details the regression from concord to conflict among the Cheyenne/Arapahoe (Tsitsistas/Hinono’ei) and whites (vi ’ho’ i) throughout the nineteenth century. His work will be immensely helpful to scholars as it condenses mountains of primary and secondary sources into a linear account of the lead-up, perpetration, and consequences of Sand Creek. His notes account for almost a quarter of the book and do more than merely cite his sources. He addresses irregularities and inconsistencies, from eyewitness testimonies to the cause of death of a white female captive of the Cheyenne. A detailed two-page map drawn by cartographer Bill Nelson in conjunction with the author’s detailed description of the massacre’s movements will be particularly valuable to a range of individuals from future historians to interpreters of the National Historic Site.

While the book is presented as a linear narrative, Kraft is at his best when he takes time to appreciate the enormity of the event he has just described. The murder of the Hungate family on their farm outside of Denver by a group of Natives in the months before Sand Creek is a well-known event to historians of the time period which the author presents blow by blow over the course of the next few pages. However, as the mutilated family’s remains were infamously displayed in Denver, Kraft pauses and allows himself to step into the shoes of the citizenry. He describes the emotions of “panic, fear, and outrage [that] seized the population with a bloodlust” (p. 141). This is the mark of excellent historical writing. Instead of moving on to the next linear occurrence, he allows his readers to pause and soak up the magnitude of what just occurred. He reminds us that while these events occurred more than one hundred and fifty years ago, the same irrationalities and venom that destroyed the Hungates and Black Kettle’s camp lie dormant within our own human nature. “History can never be static,” Kraft explains, “for if so, we will never learn the truth” (p. 369).

The author’s extensive research and attention to detail give the reader a full documentation of the complex web of events surrounding the massacre. … The reader is open to interpret how the lifeway of accommodation so tragically ended from the various aspects of Kraft’s linear progression of the narrative.

— William W. Carroll, Journal of Arizona History (Arizona Historical Society, Vol. 62, No. 1, Spring 2021)

The November 1864 murder and mutilation of over 200 peaceful Southern Cheyenne (Tsistsistas) and Arapaho (Hinono’eino’) at Sand Creek by Colorado volunteer cavalrymen was one of the great atrocities in American history. The attack was intended to be a slaughter. Its architect, Colonel John Chivington, told another officer that he “had come to kill Indians, and believed it to be honorable to kill Indians under any and all circumstances” (206).

Independent scholar Louis Kraft uses contemporary sources to reconstruct this horrific event down to the minutest of details (including his own maps), but Sand Creek really serves as the lynchpin for a broader project. In an impressively detailed and nuanced work, Kraft presents the context and backstory leading to Sand Creek as well as its aftermath, including the duplicitous Medicine Lodge Treaty, retaliatory warfare, and Custer’s Washita River massacre (where Cheyenne peace chief and Sand Creek survivor Black Kettle was killed). Utilizing a wealth of contemporary, archival, and scholarly sources, Kraft presents a rich portrait of white-indigenous relations spanning several decades in what would become the states of Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. In an epilogue, he notes the massacre’s devastating cultural legacy for Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho.

Kraft presents compelling portraits of major and minor characters and describes the social dynamics within both settler and indigenous Great Plains communities of the 1860s, including political tensions in Colorado Territory between Union and Confederate sympathizers. One of the book’s major takeaways is that local relationships between whites and Indians were not purely conflictual: there were people on both sides who tried, mostly unsuccessfully, to foster cooperation and coexistence. The book includes fascinating tidbits such as an 1861 meeting between Arapaho and Colorado leaders that culminated with them attending a play at a Denver theater. Kraft spotlights people who lived “in between,” such as William Bent, who married Owl Woman (Cheyenne), and his biracial sons, Charley and George, who lived with the Cheyenne and witnessed Sand Creek. Kraft meticulously recreates the negotiations between government officials and Indian leaders; parsing the contemporary records, he identifies where negotiators’ words were—tragically—mistranslated.

… One thing becomes clear after reading Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway: not only was the conflict between Plains Indians and the United States asymmetrical in terms of capacities, but it was also asymmetrical in intent. The Cheyenne and Arapaho wanted to maintain their way of life on some part of their traditional lands—and many were even willing to adapt to “white ways” on their land—whereas the US government and American settlers had no intention whatsoever of allowing that to happen; they wanted the land, and nothing would stop them from taking it.

— Pierre M. Atlas, Great Plains Quarterly (University of Nebraska Press, Vol. 41, Nos. 1-2, Winter-Spring 2021)

Background on the creation of the manuscript

At dawn gunfire jerked a slumbering village to life. Unprepared for the onslaught Cheyennes and Arapahos scrambled to escape the attack, and many avoided death. Those that didn’t would face a swift end. Small children were used for target practice. An unborn child was cut from its dead mother and scalped. The dead would be hacked to pieces. Most corpses yielded from five to seven scalps. Penises, vaginas, and breasts were cut from the dead and displayed as trophies.

The tragedy of Sand Creek exploded upon the frontier on November 29, 1864, but there is much more to the disaster than butchery, including the lead-up to, the battle of, and the aftermath. Viewpoints on the events were, and are, well-defined. At first cheered on the frontier as a major triumph over Indians who terrorized Colorado Territory, the attack soon became immersed in controversy that tarnished the victory, and by so doing tore the Territory asunder. This is the story of the total removal of a people from their homeland as seen through the eyes of the participants …

Cheyenne chiefs Gordon Yellowman and Cheyenne Harvey Pratt in November 2011. I met Gordon originally in 1999 and sporadically have spoken at events with him over the years. He is onboard for a documentary if ever funds can be raised. On this day I met Harvey for the first time, a day wherein he delivered a terrific talk on what it is like to be a Cheyenne warrior. The hope is to involve both Gordon and Harvey during the development of the Sand Creek manuscript. (Photo © Louis Kraft 2011)

Fine-tuning of the Sand Creek book proposal for OU Press is ongoing with editor-in-chief Chuck Rankin. As stated above, it deals with the events leading up to the attack on a Cheyenne-Arapaho village on Sand Creek, Colorado Territory, in November 1864. Wynkoop, Black Kettle, John Chivington, Left Hand, George Bent, Rocky Mountain News editor William Byers, Bull Bear, John Evans, William Bent, Silas Soule, among others, will play key roles in the manuscript. This is a story that Chuck and I have been talking about and working on a story line that is acceptable to both of us for a long time. We’re close, and soon Chuck will pitch the book, … I anticipate the signing of a contract in late spring or early summer 2013. At that point in time this book will require a large amount of my time. Although a lot of the research is in-house, one research trip has already happened in 2013 and there is still at least one major trip in my future.

As with all my books, I always keep a personal and round-robin open line with writer-historians I like and respect. At least two major players in the Indian wars writing world, and two people I count as friends, will become go-to experts. I plan on cementing these relationships in April 2013. Actually this has happened, and they are onboard with the project and my request, which makes me a happy person for I certainly respect their work and enjoy hanging out with them whenever we are in the same location at the same time. This is not to walk away from my Cheyenne connections, for they will play a much larger part in the creation of this book than they did with the Wynkoop book, and their contribution to it was huge.

November 12, 2011. Cheyenne, Oklahoma. Writer-historian Jerry Greene with LK before the doors opened to the public for the final day of the Washita Battlefield NHS symposium. Jerry and I had gone out to an early dinner the previous night, and as soon as he saw me on this morning he said: “Who dragged you through the gutter last night?” He was right, I looked like hell, but no one dragged me through the gutter, … just a condition I deal with more often than I like, and the night of November 11 was just one of times wherein there would be no sleep. On this day, both Jerry and I featured Sand Creek in our talks. (Photo © Washita Battlefield NHS 2011)

Although I’ve used the blog to publicize Sand Creek and the people that lived through those frightening 1860s days, I want to keep some of my thoughts on the process to create the story in one location.

lk with Dr. Henrietta Mann (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College, Weatherford, OK) at the Washita Battlefield 140th Celebration, December 6, 2008.The previous day Henry had seen a performance of the Wynkoop one-man show, this morning she had seen me talk about Wynkoop, and on this evening I would hear her speak for the first time. This photo was taken while we took a break from our lunch. All I can say about this lady is wow! I’m so lucky to know her and cherish every time we are together. (Photo © Leroy Livesay 2008)

I also want to make one point absolutely clear—I don’t write about villains. I am fairly safe in saying that the major players all thought they were in the right in everything they did. Both sides destroyed property, abducted, raped, killed, and mutilated. Both sides had their reasons. When a handful of whites on the frontier dared to speak out against what they considered the massacre of innocent people, they became outcasts. Hatred fueled by greed, conquest, fear, and racism dominated the conflict. The terror of sudden violence combined with the struggle to survive was real, making it one of the most complicated, compelling, and poignant times during that period we call the Indian wars. The goal is to show you what happened. If you don’t like what someone did, you label them a villain for I won’t. … My apologies for what follows.

Those of you that know my writing, have heard me talk, or have seen a performance in a play know damn well where I stand on humanity. For my Sand Creek book to succeed, you must know the key players to the events that led up to the November 1864 attack on Black Kettle and Left Hand’s villages and the tragic aftermath. I need to show you what happened. I know my view, and if you know me you know what it is, but as a writer and historian I must show you what happened without allowing my bias to interfere with the narrative. If I do my job, you’ll be able to decide what happened and how you feel about it. If I do this, I’ve succeeded.

LK as Ned Wynkoop viewing the butchered remains of the dead at Sand Creek in 1865. This image may not belong here, but it is for I love director Tom Eubanks’ lighting design for this scene as played for two performances in Oklahoma. Two colors, red and black—Stark, so stark it captures the horror of war the world over. People have complained that the image is too dark and they can’t see it. I disagree. And although I have had some fun chewing into good friend and writer supreme Johnny Boggs’ photos over the years, this is an absolutely great image. Of all the photos taken since my return to the stage, it is by far my favorite. (Photo by Johnny Boggs during a dress rehearsal in December 2008)

At times I plan on using the blog as a device to open a conversation on an incident or person wherein I need more information or understanding. The hope here is to discuss motives and actions, but under no circumstances will the blog become a repository to berate individuals or people as demonic rapists and murderers. I am not open to prejudicial views or racist prose. Let’s talk about what happened and who did what. What are the players’ fears, hopes, motivations? I hate to repeat myself here, but I am firm about the above—under no circumstances will I accept or reply to any blue prose that comes even close to a racial slur. … I will not acknowledge such posts, nor will I comment on them. There will be absolutely no conversation. My trigger finger will simply delete the offending post.

A little about how I approach the Sand Creek project

Research is ongoing, and it will continue throughout the entire research, writing, and production process of the book. Actually, it will continue after the book is published for the goal is learn and correct when what were thought to be truths don’t pan out as new or missed information provides a clearer picture of events and participants.

LK talking about “Cheyenne Indian Agent Edward Wynkoop’s 1867 Fight to Prevent War” at the Chávez History Library (Santa Fe, N. Mex.) on 15sept2004. The reason I have used this image here is because my views on race and Wynkoop have garnered me anger and hate over the years. At times when I’ve appeared—let’s say in Colorado—people will turn their backs to me. Once Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway is published I will have more problems with the ongoing racial hatred that refuses to go away in the telling of how the United States took any land it desired, and when the American Indians fought back in the manner of their culture they were labeled “savages.” Really? What about the “savagery” of the American culture? The story of my life. Hell, ladies & gents, if I can’t push you as far as I can, why bother? The Chávez has provided me with Wynkoop, Kit Carson, Errol Flynn, and Sand Creek research. I’m home whenever I’m there. … BTW, Wynkoop has been attached to the tragedy of Sand Creek from the moment that Chivington and the Colorado Volunteers attacked and destroyed the peaceful Cheyenne-Arapaho village on 29nov1864. (photo © Louis Kraft 2004)

If you have read my blogs you know that I’m a firm believer that actions (what a person does) and not statements (what a person claims he or she did) define who they are.

… And it is a struggle to obtain the research that I require to complete a book (Sand Creek will be the hardest book that I ever write). A struggle!

The Braun HIstory Library

I spent 12 days researching at the Braun History Library (Autry National Center, Los Angeles) in June 2012. The Braun used to be the Southwest Museum’s (Los Angeles) research archive but a number of years back to survive the Southwest merged with the Autry National Center. Soon the Southwest Museum will cease to exist. On August 1, 2015, the Braun shut its doors to researchers, and it will never again reopen those doors. A few years back the Autry purchased a huge building in Burbank, California (about five miles from Tujunga House). This building, somewhere between 100,000 and 200,000 square feet, will soon house the entire Southwest collection of Indian artifacts and their archival collection of historic documents. The building, which is being converted to suit the Autry’s historic artifact and primary source needs, does not at this time (10aug2015) have a date when it will open to researchers (BTW, the Autry Library, which also a great research facility, will shut down in December 2015 so that its entire collection of artifacts and documentation can be moved to the new facility). At the present time, the research center is called the Autry Resources Center (ARC), but if someone comes up with a $5, $10, or $20 million donation to the Autry I’m certain that the ARC will be renamed.

Kim Walters doing research at the Braun History Library on 18Jun2014. As it was one of the days that I was there researching we were able to spend some time together. (photo © Louis Kraft & Kim Walters 2014)

I’ve been doing research at the Braun dating back to at least 1998—Apache wars and Cheyenne wars research (primary source documentation as well as historic images). I love the Braun (as well as the Southwest Museum) and am saddened that it is no longer available to do research. … At my first research visit I met Kim Walters, who I believe was then running the Braun Research Library. I don’t remember her title in the 1990s and it has changed and grown over the years, as would our relationship. In June 2014 her title at the Autry was “Ahmanson Curator of Native American History and Culture—Autry National Center.” She is now a friend for all time even though recently she parted ways with the Autry.

On 7aug2015 I received a portion of the research I requested at the Braun in June 2014 (fully half is still to come). Am I a happy camper? No. That said, I didn’t bitch and moan or screech out in anger. The Autry’s whatever (and I’m being and here) prevented Liza Posas and Manola Madrid from completing my research request in a timely manner. Not their fault.

In August 2015 I posted a variation on the following elsewhere on social media:

| TO ALL THE HISTORIAN CLOWNS THAT CAME BEFORE ME |

| … And I’m only talking about a small number of people for most historians aren’t clowns and try to do their best. That said, often—way too often—a clown doesn’t do proper research and what he or she created is printed and then accepted as truth. End of subject? No! … Ben Clarke (yes that is the correct spelling of his last name and I can prove it easily 100 times over in his own hand) has come down through history as Ben Clark (and he functioned as George Armstrong Custer’s chief of scouts at the Washita Battle in 1868, which resulted in the tragic death of Cheyenne chief Black Kettle and many other Tsistsistas, as the Cheyennes call themselves). Even the great researcher Walter Camp messed up his last name. Clarke married into the Cheyenne tribe and lived with them for decades. Best yet, he was an educated man.

Even got to spend good time with Marva Felchlin, who is the director of the Autry Library (at least I think that is her title). … Since saying goodbye to her and then Manola on Friday, August 7, 2015, I’ve been leaping into the air and clicking my heels … while I categorize my new material (some of which will prove to be gold—pure gold) and pound away on my iMac’s keyboard. Facts are filled in and the word flow that I want in Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway moves forward at a steady pace. |

Yep, I was talking about prime research material that I’ve been lucky enough to discover.

John Monnett and 2014 Sand Creek research in Colorado

For the record, a good portion of this section has been pulled

from one of my blogs. Reason: Blogs come and go

(that is, readers must search to find previous postings),

but the pages on this website are static and available to anyone

who visits the Louis Kraft writer website.

John Monnett is one of the top Cheyenne wars historians writing—yesteryear or today. We had met years back, and it was most likely at a western history event. We knew and liked each other but had not become friends until both of us spoke at an Order of the Indian Wars symposium in Centennial, Colorado, in 2010. At a party afterwards we hung out and got to know each other. From then on our friendship has grown. Previously John had provided me with a great peer review of the Wynkoop manuscript (Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek, OU Press, 2011) and later a top-notch peer review of the proposal for Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway (OU Press). For those who don’t know what a peer review is, it is: 1) If it is a pitch for a book contract it is to get a thumbs up, and more important 2) It is to obtain constructive criticism on how to both improve the manuscript and correct errors in it. When I told John that after my wife Pailin Subanna-Kraft (a page dedicated to Pailin will soon appear on this webpage) obtained her Green Card that we would be making a research trip to Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas. John didn’t hesitate, and immediately invited us to stay with him and his wonderful wife Linda.

LK talking about Ned Wynkoop lashing out at the U.S. government for the murder of what he considered innocent people (Read the Cheyennes) in December 1868. See the above image of lk with Jerry Greene to see why I look like death done over. This is not new with me. In fact it has been a part of my life for well over a dozen years. That said when it is time to deliver I deliver. (photo © Washita Battlefield NHS 2011)

As most of you know I write about people, but now I’m now faced with a much larger task of making more people leading players and at the same time connecting them to the supporting players while maintaining a flow in the manuscript. This task is a massive one. Who, where, when? … While at the same time showing and not telling (a key to any writing). The goal is to transition smoothly between the players and the events. Doable? I have every intention of making this happen. If I fail my publisher—read my editor and friend Chuck Rankin—will do what he can to get me back on track. If I again fail, I’m certain he’ll say: “Adios amigo!” I have no intention of failing.

Actually this is the best challenge I have ever faced, and I love it.

After surviving a snowstorm on the I-70 in a car that was built for speed and handling but not for weather on September 29, 2014, John and Linda welcomed us into their Colorado home and lives.

John Monnett is a terrific fellow and I count myself lucky to call him a friend. John at times hasn’t been pleased with some of my photos of him. Hopefully he likes this image for it is one of my favorites of him.

Beginning the next morning John became Pailin and my private tour guide and curator to the subject of the Southern Cheyennes and those oh-so key years of the mid-1860s. Our first stop was the “Chief Niwot Legend & Legacy” exhibit at the Boulder History Museum. Niwot (or Left Hand, which is his name that is most known) was a chief of the Arapahos during these key years. All I’ll tell you about Niwot is that he will be featured as much as possible in Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway and that he received wounds during the November 29, 1864, attack on the Sand Creek village and that they led to his death. This man stood for peace and had done all he could to bring about an end to the 1864 Indian war in Colorado Territory.

This visit to the Boulder History Museum was Pailin’s introduction to research. Over the coming days I wore her out with what I requested she do, but she came through admirably.

Be careful with what you read online regarding Niwot, for some of

the supposed factual information you’ll see is flat-out not true.

Actually it is wise to heed this advice when researching many of the

historical figures involved in the American Indian wars online.

John introduced us to local history as related to Sand Creek, and then he and Linda took us to the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, which is in the middle of “no where” Colorado.

I don’t remember what John Monnett was saying to seasonal ranger Jeff Campbell, but I’m certain that it opened the door to additional words. With luck Mr. Campbell can get by my less than satisfactory review of a Park Service document that was piss-poor at best (and the National Park Service asked me to review the document). My review was constructive, but unfortunately the U.S. Park Service has their thumb stuck where the sun doesn’t shine and has absolutely refused to listen to constructive criticism. Time heals all wounds; if not, it will lead to future unpleasantries. (photo by Pailin Subanna-Kraft; & © Pailin Subanna-Kraft, John Monnett & Louis Kraft 2014)

Unfortunately, this NHS needs a lot of money to bring it up to Washita Battlefield NHS (Oklahoma) in scope, presentation, and splendor. Along with the Washita NHS and the Fort Larned NHS (Kansas), which has a strong connection to the peaceful Cheyenne-Dog Man-Lakota village that Gen. Winfield Hancock destroyed in 1867, Sand Creek Massacre NHS rounds out the three most sacred Cheyenne sites on the central and southern plains.

The Sand Creek NHS is still basically closed to the public, and that includes historians (and charlatans who create history in their image). Unfortunately the Sand Creek Massacre NHS is a project of consensus. Former murder investigator and seasonal Sand Creek NHS ranger Jeff Campbell’s dissection and reassembly of the events on that tragic November 29, 1864, day should not be ignored, and this location should not be open to a round-robin consensus of multiple-party egos and partial truths (often based upon the retelling of history that at times isn’t even bad fiction, and I’m not pointing my finger at just Cheyenne and Arapaho oral memory). That said, this is sacred ground and it deserves a visitor center/museum that matches the one at the Washita. The land is magnificent, and the bluffs that skirt the western perimeter of the property present a marvelous view of massiveness of the ground on which the attack on a peaceful Cheyenne-Arapaho village took place. There are no well-placed signs along the high ground telling the visitor what he or she is looking at to date, so one must have a good knowledge of what happened to make any sense of what is seen.

This image is a “selfie” by Pailin’s iPad on 3oct2014. Other than her, the rest of us didn’t know that this image was being taken. From left: Pailin, LInda & John Monnett, and LK. The four of us are at the second and final bench on the walk skirting the village site. John is checking the brochure, which has a small map and I’m asking Pailin what she is doing. “Taking a photo,” she replied. “Huh?” We had great temperature for exploring but the sun made for deep shadows. (photo © Pailin Subanna-Kraft & Louis Kraft, Linda & John Monnett 2014)

To gain an understanding of all the parties involved in the massive project of purchasing the land, creating the NHS, and then piecing together all the historical events has been a joint project with many factions involved, read Ari Kelman’s book A Misplaced Massacre: Struggling over the Memory of Sand Creek (Harvard University Press, 2013).

Although Kelman’s prose is a page-turner when dealing with the events of the last 30 or 40 years as he brings the modern-day Sand Creek story together—and it was a fight for the Cheyennes, Arapahos, U.S. government, land owners, historians, would-be historians (and some are charlatans), and the National Park Service to create this historic site—be wary of Kelman’s information related to the battle itself and the events surrounding it. Although Kelman uses, at least his notes claim he used, primary source material, there are many errors. Why? I don’t know why. Perhaps there was a poor understanding of the primary source material, or facts weren’t checked, or there was a rush to get into print before the 150th anniversary of the mass murder of people who thought that they were at peace? There is a warning here. While in modern times and dealing with the fight (and it was a fight) to create this much-needed NHS that protects this oh-so-sacred ground, Kelman’s book is a wonder. However, if writing about the participants and events of that horrific time during the 1860s be careful or you will repeat Kelman’s errors.

Pailin Subanna-Kraft doing something she loves—documenting what is happening. On this day (3oct2014), she documented our visit to the Sand Creek Massacre NHS. A good day for her, Linda & John Monnett, and LK. (photo © Pailin Subanna-Kraft & Louis Kraft 2014)

The November 1864 attack on the village quickly turned into a running fight as the Cheyennes and Arapahos tried to flee while the soldiers killed and hacked to pieces every living being that looked like an Indian—man, woman, or child. When you walk the bluffs above the grounds you can easily see the immensity of the village site and the open expanse on which the fight took place.

LK leaning against the initial (or ending placed) at the Sand Creek Massacre NHS on 3oct2014. (photo by John Monnett and © John Monnett & Louis Kraft 2014)

I could envision myself as Capt. Silas Soule or Lt. Joseph Cramer of the First Colorado Volunteer Cavalry as they instructed their men not to fire their weapons; I could envision myself as mixed-blood Cheyenne George Bent as he scrambled to escape the surrounding soldiers only to be wounded but still able to escape under the cover of darkness.

I can also easily see myself as mixed-blood Cheyenne Edmund Guerrier as he escaped unharmed; I can imagine myself as Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle who under the cover of darkness returned to where he thought he’d find his dead wife Medicine Woman Later only to find her alive and with her escape; and finally I could picture myself as Arapaho Chief Niwot (Left Hand) as he received the wounds that would lead to his death. … I can’t visualize myself as an officer or soldier that killed women, children, and men and then cut off their sexual body parts to display as trophies of war.

This image of Pailin Subanna-Kraft & LK was taken by my great friend Glen Williams in the front of his gorgeous Dentin, Texas, home at the end of our Sand Creek & Kit Carson research trip on 12Oct2014. Even though the movement of Palin and I make the photo out of focus it is one of my favorite images of all time as it captures Pailin’s and my relationship. (photo © Louis Kraft & Pailin Subanna Kraft and Glen Williams 2014)

As Johnny Boggs’ quoted me in his terrific article, “Trail of Tragedy”

(True West Magazine, November 2014 issue, page 53), “War

doesn’t give soldiers the right to murder, rape, and butcher.

Not yesterday, not today, and not ever.” Actually he

quoted me extensively in the article.

You know where I stand, but as a writer and historian

I must separate myself from the story and let the participants’

actions speak for them. I must eliminate my bias from the

writing and reporting, for whatever I think and feel is not the

same as what the people thought and felt in 1864. If I

do my job properly, the readers will make their

own decisions on what happened.

| Louis Kraft writer © Louis Kraft 2013–2024 |