Website & blogs © Louis Kraft 2013-2020

Contact Kraft at writerkraft@gmail.com or comment at the end of the blog

The best place to start is with a little background of something that doesn’t exist anymore (at least not as it was, and sometime in the not-too-distant future never again). As I type these words I’m sad. The city of Los Angeles had something special.

The Southwest Museum of the American Indian, which is now part of the Autry National Center of the American West. (art © Louis Kraft 2014)

Writers of history and especially the American Indian shame on you. The diverse population of the city of Los Angeles, which I believe still has the largest Native American population not living on the Rez (most likely the Navajo Reservation, as it dwarfs the other reservations), I’m ashamed of you too. But more I’m ashamed of the city and the county of Los Angeles, for you had a treasure and you didn’t support it. Shame on you!!!!

Los Angeles, you constantly brag about the quality of culture that exists within the city and county borders. We have everything. Great museums, great theaters, great restaurants (I think every food possible, sans one—American Indian; how many times do I have to say that damned word, “shame”?). And let’s not forget the mountains, surf, and weather that are to die for. Yes, we do have a number of days during summer and a number of them string together and the temperature is an ungodly 100+ degrees, but these have shrunk in number over recent years. We don’t compare to Phoenix and the rest of the Valley of the Sun; for unlike the residents of that sprawling metropolis the people of LA don’t fry their eggs on the pavement (that’s right; lk isn’t seeking any kissy points from Arizona; the only establishment that welcomes him back is Guidon Books in Old Scottsdale). Oh, I should add that Christmas time is shorts and broad-brimmed hats, and if you still have your American football legs (mine were during the days of the late-great Johnny U. and Joe Montana) a round of competitive tossing and catching the pigskin after a Christmas dinner under blue skies in mid-70 to low 80 degree weather with 20 or so buddies often happened.

Charles Lummis, the American Southwest, and well you know, … the future

Charles Lummis (1859-1928) earned a living as a journalist, but without doing due-diligence research I wonder how much family money he had.

This image for this magnificent exhibit that the then Autry Museum of Western Heritage presented for a little over three months in 1996 represents what the Autry had been and what the 2003 merger with the Southwest Museum can become. Friend Paul Andrew Hutton played a major role in this exhibit coming to life. It was by far the best exhibit that I have ever seen at the Autry or the Southwest. Let us hope that the merged museums can again recreate this type of excellence. I saw the exhibit twice; first with my good friend writer/historian Eric Niderost and later by myself. … Over the years the Autry would create another masterpiece, but I believe most of it came from in-house—they paid a long-overdue homage to Gene Autry a few years back. Alas, it is long gone, but it should have been made into a permanent exhibit, and this is coming from someone who didn’t like Gene’s singing, B-moves, or what is now called the “Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.” Hell, I guess that I now live in Anaheim of North Hollywood, Los Angeles. (photo © Louis Kraft 1996)

I’ve not met many rich journalists. In direct relation to what he would do, Lummis stood for Indian rights and historic preservation. He was also an historian, photographer, ethnographer, and archaeologist. He had a passion for the Southwest and the Indian people that called this land home.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Charles Lummis, who was the driving force behind the Southwest Society, saw the creation of a museum that would house art, history, and science of the American Southwest. The Southwest Museum opened in downtown Los Angeles in 1907. Seven years later it moved to its current location at Mount Washington on the western side of the Arroyo Seco, and in which in the coming decades the 110 freeway would snake through and connect downtown Los Angeles with the city of Pasadena in the San Gabriel Valley. Sumner P. Hunt designed the original structure in the style of Spanish Colonial Revival that climbed the hillside. Over the years additions would be added. The Braun Research Library opened in 1979. If one doesn’t drive up the hill to the parking lot, he or she can walk from the subway just below the famed institution to a tunnel that leads to an elevator that rises 150 feet to the bottom floor of the original structure.

The Braun Research Library is one of the premier archives that I have spent many hours, days, months, and more visiting in an attempt to learn what is hopefully the truth. Other than the Braun here are other classy archives in which I’ve researched:

- The Fray Angélico Chávez History Library (Santa Fe, N. Mex.)

- USC Warner Bros. Archives (Los Angeles, Ca.)

- Arizona Historical Society (Tucson, Az.)

- Western History Collection, Denver Public Library (Co.)

- History Colorado (Denver; I have not researched there since the new facility opened)

- Fort Larned National Historic Site (Larned, Ks.)

Of course, there is a disclaimer here, and it is as follows. Sometimes it is more economical to order research. National Archives (various locations) and Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. are two such library-archives.

A long and winding road to the Braun Research Library

Let’s drift back to the dark ages. In 1987 I spoke at the Order of the Indian Wars (OIW) “First Annual West Coast Indian Wars Conference” in Fullerton, Ca. (alas, it was the first and only OIW SoCal conference).

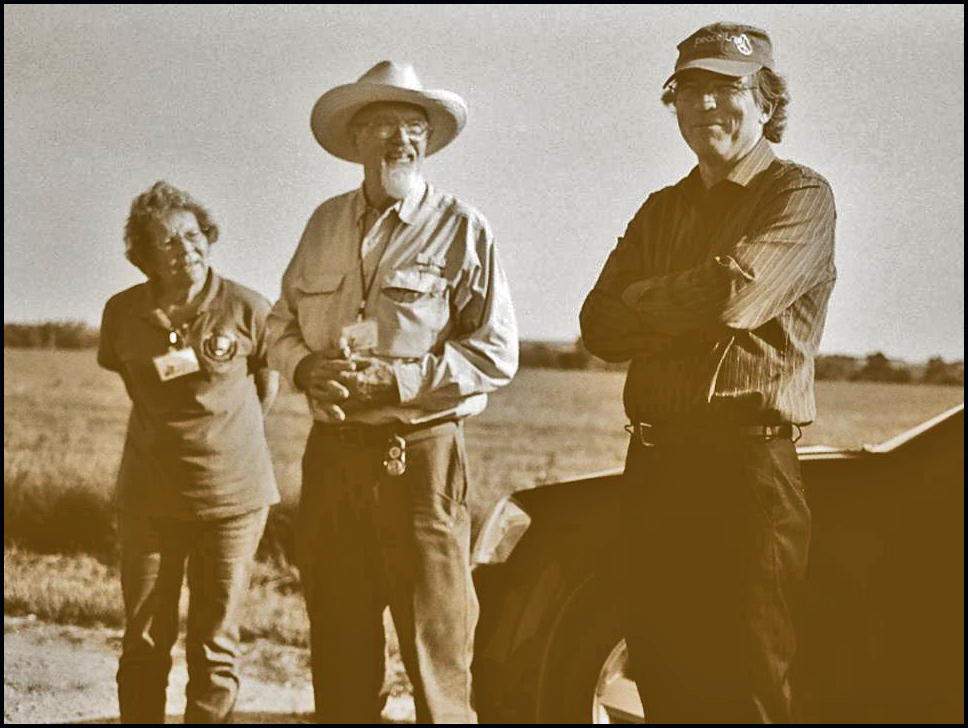

Jerry Russell holding court on private property above the supposed Sand Creek village massacre site in 1987 (see photo of Marissa Kraft, below, for more about this visit). (photo © Louis Kraft 1987)

This event cemented my relationship with Jerry Russell, who ran the OIW and who always had my back covered.

Jerry is long time gone, and I still miss him. At that conference I met Mike Koury (The Old Army Press), a great speaker (he should do it more often), who took over the Order of the Indian Wars after Jerry’s death. Mike and I became friends and for years and years he has done everything possible to help my writing. I also met Chris Summit, former historian at the Custer Battlefield National Monument (since renamed to the Little Bighorn National Monument). He was round and perhaps short. I thought that he would make an impact on Indian wars writing, but he dropped from sight (don’t know why; hope he is well). The reason I mention him is because during the two-day event (February 28-March 1) he told me that I should check out the Braun Research Library at the Southwest Museum for it would be a boon to my Cheyenne Indian research.

I never forgot Chris Summit’s words.

Years passed and believe it or not, with the publication of Custer and the Cheyenne (Upton and Sons, Publishers, 1995), a quirk of fate thrust me into a 10-year quest to understand a long-forgotten 6th U.S. Cavalry officer named Charles Gatewood and his involvement with White Mountain and Chiricahua Apaches. A Custer book signing at Guidon Books, in Old Scottsdale, Az., alerted me to the Gatewood Collection at the Arizona Historical Society in Tucson. The following month resulted in a nine-day trip to view the Gatewood Collection (over the years I would spend another three+ months at the archive).

Enter Kim Walters

Gatewood had preempted what I thought would be my next Indian wars book (soldier/Indian agent Ned Wynkoop and his relationship with Cheyennes and Arapahos). In the late 1990s I took off the Gatewood/Apache blinders and heeding Chris Summit’s suggestion contacted the Braun about doing Cheyenne research as related to my longtime project on Wynkoop.

This is when I met Kim Walters.

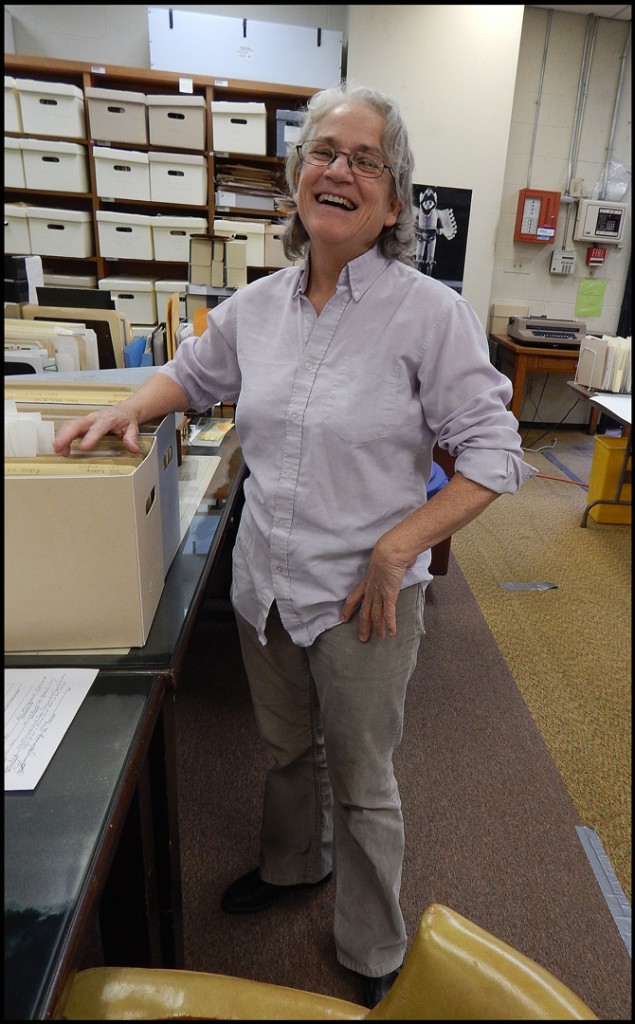

Kim Walters doing research at the Braun on June 18. I hadn’t seen Kim since the Wynkoop book had been published and it was good to see her again. Her current title is: “Ahmanson Curator of Native American History and Culture—Autry National Center.” (photo © Louis Kraft and Kim Walters 2014)

At that time Kim’s title was “Director, Braun Research Library,” a title she held from 1990 until 2011. She quickly became my go-to person. My sole interest during these visits to the Braun was the Cheyennes in Wynkoop’s life. With Kim’s terrific digging I became privy to prime Cheyenne research in the George Bird Grinnell Papers. At the time I didn’t know of a 77-page document that lists Grinnell’s Papers (and don’t think it existed in its current state then).

Head Librarian Liza Posas shows lk where the George Bird Grinnell Papers are stored in the Braun’s stacks. Liza and I have discussed me submitting suggestions that will aid the 77-page listing of Grinnell’s papers, among other things that are not for this blog. The suggestions will not be egotistical; simply constructive comments that will hopefully aid researchers in the future. (photo © Louis Kraft and Liza Posas 2014)

I would not see this extended list until Braun Head Librarian Liza Posas supplied it to me earlier this year (see below for more on Liza). Good digging by Kim!!! And especially so since the key documents she located for me are not listed in the contents of the Grinnell Papers. That said, they are in the folders listed in the 77-page Grinnell Papers document (I checked to ensure that they were still located in the same folders). The information that Kim found for me saw print in Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek (OU Press, 2011).

Soon after completing the Cheyenne Indian research for the Wynkoop manuscript I returned to the Braun to search for images for Gatewood & Geronimo (University of New Mexico Press, 2000), and again I struck gold in various collections with Kim’s help. The images included:

- A little Apache girl about four years old holding a small puppy (perhaps my favorite image ever in any of my publications for I could write a book about her)

- A studio portrait of Gen. George Crook (1880s)

- The Chokonen Chiricahua Apache chief Chihuahua

- The Chihenne Chiricahua Apache war leader Kaytennae w/Benito

- The mixed-blood Mexican-Apache Mickey Free

- The Chihenne Chiricahua Apache Mangus

Moving forward

The Custer book tossed my name into the hat, but it was Gatewood & Geronimo that made me a player. Kim Walters and the Braun helped make this happen. Thank you, Kim.

Custer and the Cheyenne had been contracted but G&G was spec. I figured I didn’t have a good enough name to move away from regional presses and submitted the manuscript to Westernlore Press (Tucson, Az.). It was immediately accepted, and I said I wanted a contract. “I’ll get to it, when I finish one of my books,” Lynn R. Bailey told me (he was also a writer). I gave him three months and repeated my request. He told me he’d get to it when he was ready. I fired him, and that day sent a query letter to the University of Arizona Press. I waited a week. Nothing happened. I sent a query to the University of New Mexico Press.

(left to right): Bonita & Dr. Leo Oliva (more on good friends Leo & Bonita in an upcoming blog), and Dr. Durwood Ball. After Leo and I spoke at the Pawnee Fork village site (he about the events that led up to Gen. Winfield Hancock destroying a Tsistsista, Dog Man, Lakota village on the Pawnee Fork in Kansas in April 1867 and I about Wynkoop’s effort to save the village), Durwood followed us back to Fort Larned so he could see the hill that Hancock’s army climbed on April 14, 1867, only to halt when they saw the battle line of Cheyennes and Sioux in the valley. Wynkoop asked permission of Hancock to ride between the lines and sooth Indian fears. Edmund Guerrier, a mixed-blood Cheyenne, rode into the valley with him. Durwood spoke that night about Col. Edwin Vose Sumner, the subject of his next book. BTW, the photo is black & white, and with the late afternoon sun everyone was in deep shadow. I turned the image into a duotone and lightened it. (photo © Louis Kraft 2012)

Durwood Ball, then editor-in-chief at University of New Mexico Press, contacted me immediately; he wanted the G&G manuscript (the U of A Press contacted me a week later; am sorry—too late). Durwood, like Jerry Russell, always had my back, especially during the production process which had a few bumps. I don’t see him near enough, but whenever we are together it is like we are neighbors and hang out on weekends.

A quick return to the Braun, but not in person

I had less success at the Braun with the second Gatewood book, Lt. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir (University of Nebraska Press, 2005). I had wanted to use the same Apache girl image again in this book, and started the process perhaps three months before my deadline but due to problems with the Southwest’s schedule (nothing to do with Kim) I couldn’t secure the needed documentation to proceed with the publisher. The deadline arrived with nothing from the Southwest. No big deal for I always have another 10 or more images that I want to use with documentation in place if an alternate is needed. Problem immediately solved. I wrote fully two-thirds of the text and the remainder is my editing of Gatewood’s long-winded and very passive prose. This volume is by far my best-selling book (I think in large part as the publisher promoted it aggressively).

Chuck Rankin, the Cheyennes, and the tragedy of Sand Creek

For me writing nonfiction, real nonfiction, is a long-term process. Put another way, it is not wham bam, thank you ma’am. What does this less than satisfactory statement mean? I must put in the time and walk the walk to know what I’m writing about.

This section needs to lead with a major disclaimer. Chuck Rankin, editor-in-chief at OU Press, is a good friend. He has also played perhaps the most key role in my Indian wars life, and this includes my writing not with OU Press. He liked my last blog with a lone criticism; he did not like the image I posted of him. Chuck has told me many times now that he prefers to reside in the shadows and not in the limelight. I do my best not to talk about him, but damn!, if you could only use one word to describe me as a writer it would be biographer. Chuck, I can’t help myself. It’s what I do.

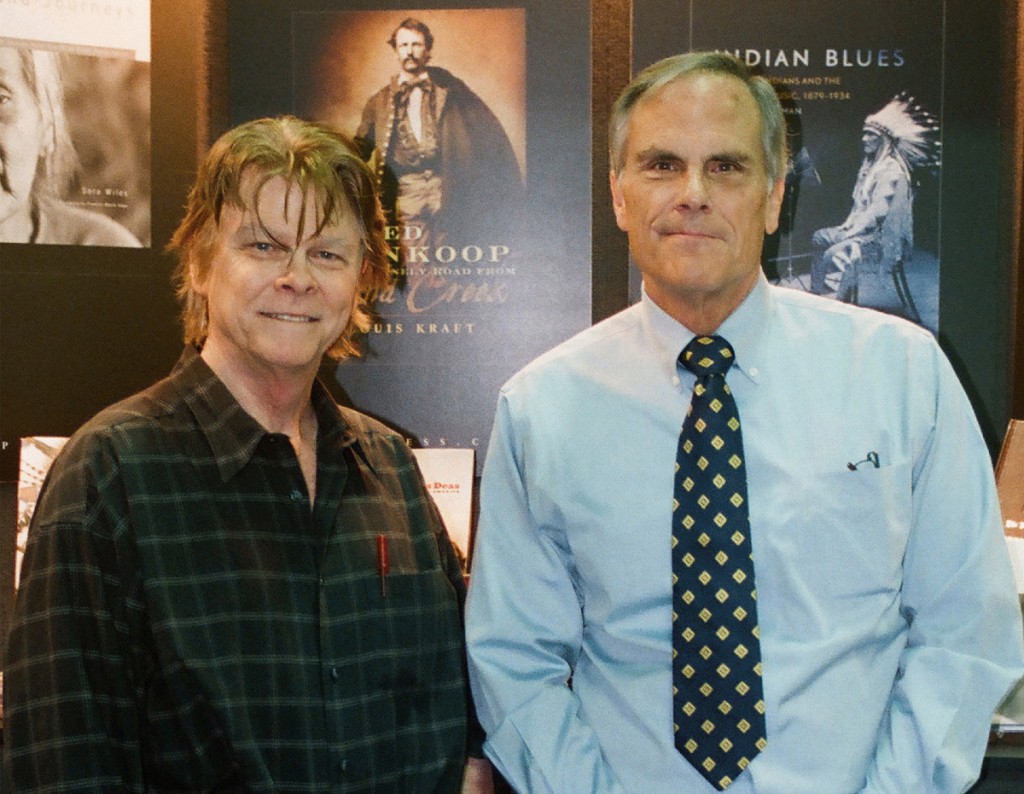

lk with Chuck Rankin on 15oct11 at the Western History Association convention in Oakland, Ca. Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek became available to the public in Oakland. Chuck gave me the book poster behind us. I framed it and it resides in my living room at Tujunga House. I know Chuck doesn’t like this type of publicity, but he does great work and any writer who works with him is damned lucky. This should not remain in the shadows; it should be proclaimed! (photo © Louis Kraft & Chuck Rankin 2011)

Right around the time that Chuck and I signed the contract for the Wynkoop book (without checking, I think 2005), he started pitching me on writing a book about the Sand Creek Massacre. I said, “No, I don’t write books about war. I write about people.” He pitched again and eventually we began to talk about the possibility of a book. Sometime before the Wynkoop book was published I pitched him on a “people” book, and the conversation continued. We came to a verbal agreement on the storyline about the time the Wynkoop book saw print. It took me almost another two years to create a 36-page proposal that was satisfactory to both myself, Chuck, and OU Press. During the entire time Chuck supported the project 100 percent. His input and patience were exceptional. Two reviewers also provided constructive criticism (one being good friend and great Indian wars historian John Monnett).

Unfortunately I won’t tell you about the storyline.

My daughter Marissa and I had been tracking Custer when Jerry Russell’s OIW traveling tour ended at the supposed Sand Creek Massacre site on private property in 1987. I called Jerry and asked if we could join the trip to Sand Creek and following banquet. He graciously said yes. This actually turned into an article for True West (1990). While the tour assembled on the bluffs, Marissa and I explored the land below. There were rattlesnakes, including babies. She isn’t looking at one here. (Photo © Louis & Marissa Kraft 1987)

Without telling you anything I need to pull the Tsistsistas from the mists of time and into their golden age, and as soon as possible I need to make the story people driven.

More, I must interlink people story lines. When you have one or two lead players this isn’t a hard task. However, when you increase the major player count to 10 or more, this task becomes complicated. To make this work I must know the leading (and supporting) players intimately, for only then will I be able to move about in the story smoothly. Research, research, and more research is the key (and this is mixed with writing and rewriting every step of the way).

For all my research and writing dealing with white/Cheyenne relations and history (and this dates back to the dark ages), there is still a lot that I don’t know about the Cheyennes (and to a lesser degree about the whites and mixed-blood players). This is a no-brainer; I must increase my knowledge about the Cheyennes and others.

The Braun becomes a major player

Liza Posas, Head Librarian

When I contacted Kim at the beginning of the year regarding revisiting Mr. Grinnell’s Papers she informed me that she had moved on at the Autry. She pointed me to Liza Posas, copied Liza on the email, and suggested that she send the 77-page Grinnell listing. This marked the beginning of my relationship with Liza (I believe that it was in February).

John Monnett at The Fort on 10apr13, a cool restaurant in Morrison, Co., that serves venison, rattlesnake, buffalo, and so on. He may look like a dreamer, but he’s actually a very good listener. (photo Louis Kraft & John Monnett 2013)

My friend John Monnett constantly has Cheyenne manuscripts in progress, and we had talked about my return. When he learned of the extended list he asked to see it, and Liza sent it to him. Months would pass before I could visit the Braun and meet Liza and Research Services Associate Manola Madrid (more about Manola below). Liza and Manola prepared to work closely with me to ensure that I saw what I wanted/needed to see.

No Kim. Shock, pure shock? No, not at all. This might have been my first reaction to a change that I didn’t expect, but it vanished beginning with Liza’s first contact with me.

During our initial emails she partnered with me to ensure that I was primed for a successful search regardless of the final outcome. What? What does “I was primed for a successful search regardless of the final outcome” mean? Just this: If I find documentation I can use, great; but if not, and I am certain that I have looked at everything that is related to my search and found nothing, I have also succeeded. Huh? That’s right, I have succeeded for I no longer need to worry that I missed something because the search was not complete, that is I didn’t look at everything.

To repeat, and I’m talking about Liza here, her lone goal was to help my research succeed. And when I met her late on that first day—wow! I met a person who was not only involved and interested but would be available (even though she had to spend time at the Autry across town). And more, she’s a fun and positive and bright individual. The Braun has a first class person performing a needed task of ensuring that our history—yours, mine, and specifically in this case, the lifeway and history of the Cheyennes will continue to survive.

This is my MacBook Pro on the first floor of the Braun at the beginning of the day on 18jun14. You can see the open balconies of the second floor. I spent a good amount of my time at this table and to a lesser extent the other tables in the room. Intense work is about to begin. My kind of workplace! (photo © Louis Kraft 2014)

Liza okayed some research for John Monnett, and it happened. The year 2013 gave John and myself time to cement our relationship thanks to our mutual friend Layton Hooper, who only became my friend that year when he and his wonderful wife Vicki opened their home to me in Fort Collins, Co. I think it was for nine days (or somewhere close). Good times, times I want to repeat (if not in their new home in Arizona then at Tujunga House). Ditto you John M.

I will say this; I have always put in the time and have walked the walk. More important, none of my books are based on a preconceived thesis that I must prove at all costs. You would be shocked if you knew how many so-called historians work from a set premise and everything they write and every citation they use only sees print because it supports what they are selling. Worse, some of these historians cite fiction, create quotes, and facts that don’t exist. This discussion is not for here but will appear in a future blog.

Manola Madrid, Research Services Associate

Manola Madrid greeted me at the guard station in the Southwest Museum on my first day back at the Braun. She had worked with me in the past and we had an instant connection. On this day we worked on the third floor.

Manola Madrid on the third floor of the Braun. On this day, June 9th I worked at the table facing the Braun’s stacks. During a break she and I chatted. I asked if I could snap a few photos and she was open to the idea. It was at this time that we discussed John Wayne and his portrayal in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956). Photo © Louis Kraft and Manola Madrid 2014)

Like Liza, Manola was and is a delight to work with (Liza spent her morning at the Autry but returned to the SW Museum that afternoon and we officially met). Manola is a wizard with the archival material and she always had what I wanted to view ready upon my arrival. We have a lot in common and often when I came up for air from my prolonged and intense viewing of pages we chatted. And our subjects freely drifted and swirled about in what caught our interest at that moment. Overall I think highly of John Ford’s film The Searchers for how it explores racism on the frontier. John Wayne is brilliant; I only like one other of his performances (She Wore A Yellow Ribbon). Manola had a different take on the film, and that was the portrayal of the Comanches wasn’t very good and that over the years Ford did not portray the American Indians in a positive way. I agree with Manola.

Still, Manola’s view doesn’t diminish Wayne’s brutal portrayal of a man who lives on hate but who must find his own soul or murder his kin whom he spends the entire film searching for as she has been tainted living in captivity. For me the film works because of the murderous hatred that drives Wayne’s search but more importantly because an ingrained love for a child now an adult is strong enough to prevent murder. This story premise is strong and overrides the clichéd portrayal of the Comanches (but then the story is told through Wayne’s racist eyes). A strong-strong piece of storytelling.

If you haven’t seen it, you must.

Hanging out with Liza and Manola at the Braun

When I research I become a predator; that is I’m a hunter for information.

Manola Madrid working on Kraft’s photocopy request on 18jun14 (this will easily take her deep into July). One thing I learned a long time ago, a researcher must “work smart.” That is, he/she must document what they see while ensuring that they request copies of what they can’t transcribe error-free during their allotted time at the archive. (photo © Louis Kraft and Manola Madrid 2014)

I’m searching for people and actions and I’m not locked into Tsistsista Chief Black Kettle or Northern Tsistsista warrior Roman Nose or Dog Man Chief Bull Bear (although anything that I can find about them that I don’t know is gold). Dog Man Chief Tall Bull is always on my wanted list but he is good at avoiding detection. There is a fifth player who has appeared in three of my books, Stone Forehead. But this search at the Braun (and it will continue at least three-fold in the future) I’m open to experiencing a people and lifeway that I don’t fully know. To date the Braun hasn’t provided much on High-back Wolf (at least not yet). His death, although I think I know how and why it happened, is shrouded in mystery (read: stories that don’t coincide).

Early on I became overwhelmed with letters from George E. Hyde, who wrote A Life of George Bent written from his letters (OU Press, 1968). I requested (I thought) one folder of letters, and that was all I expected. There were more. Four, five, six, more (?) … I didn’t count, and all with the same folder number but with a letter or number extension (Hyde pops up throughout Grinnell’s papers). The letters are a marvel. There are copies of Grinnell’s letters to Hyde (but few in comparison). Ladies and gents, in case you don’t know it Hyde worked as a writer-editor for Grinnell (not once, but at least twice over the years).

The lk hardbound of the seventh printing of the OU Press reprint (1983) of Grinnell’s 1915 classic book.

Here’s my humble opinion on what I saw: George Hyde should have had a writing credit on Grinnell’s book The Fighting Cheyennes, and I believe he should have had the leading credit. How’s that for a piece of heresy? Why? How? I’m sorry, but this was not what I searched for (I took only a few notes from this for a book that I’ll never write unless I live to 100).

… Obviously Hyde functioned as a ghost writer (and he provided ranges in his negotiated fees). What follows are paraphrases from what I saw of Hyde’s work for Grinnell (and they did not come from what I saw in the original Hyde folder I viewed):

- Hyde informed Grinnell that the 17 page chapter he provided was loaded with errors, all of which he corrected. He then rewrote the chapter and it grew to 23 pages.

- Hyde submitted a chapter that he wrote from scratch upon Grinnell’s request (and this was not a lone instance).

I wonder how Hyde felt about with how Grinnell recognized his contribution to The Fighting Cheyennes: “Mr. George E. Hyde has verified most of the references and has given me the benefit of his careful study of the history of early travel on the plains.” That’s it. The quote is from: Reprint 1915. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, seventh printing, 1983, x.

If I were George Hyde, I wouldn’t have been pleased.

A question for thought: How many of the words in The Fighting Cheyennes are Hyde’s and not Grinnell’s?

I must state that I’m not belittling Grinnell. He was adventurous and went after what he considered important, and by so doing carved out a highly successful and extraordinary life and career.

**********

The lk copy of volume 1 of the hardcopy reprint of Grinnell’s 1923 two-volume classic (New York, Cooper Square Publishers, Inc., 1962), The Cheyenne Indians: Their history and ways of life. Of course Grinnell adds firepower to the misspelling of Ben Clark’s name (see “A surprise discovery”) Even though Grinnell received letters and invaluable help from the Indian wars scout and Cheyenne interpreter, he misspelled his name in the Preface (I’ve seen what I’m about quote in more recent paperbound versions of the book, in an Introduction). Grinnell wrote (p. xv), “In the South, Ben Clark helped me.” Three paragraphs later (xvi) he stated, “I owe much” to my interpreters, which included Clark, among others. … I can’t see Grinnell making this blatant spelling error; could it have made it into the printed book due to erroneous editorial insistence upon spelling Ben Clarke’s name without an “e”? Probably.

That first day I moved away from Mr. Hyde (he would pop up again and again, and sometimes in a totally surprising location). Manola was cool with this, making it clear that she would provide whatever I wanted to see.

And see I would do. And this would include early Cheyenne life and migration that I had not seen in book form. I would also see tidbits of key players that I didn’t know.

A surprise discovery

Ben Clark was Custer’s chief of scouts during the attack on Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village on the Washita River in Indian Territory on November 27, 1868. Ben Clark and George Armstrong Custer did not get along, but I have seen primary source information that Clark provided and it was key to me writing Custer and the Cheyenne for Upton and Sons, Publishers. Guess what? The primary source information was listed as Ben “Clark,” as has been every reference in book form that I have seen on Clark. Oops!!! Ben Clarke—that’s right “Clarke”—was a very literate man. He not only could write good sentences that are intelligent, his handwriting was extraordinary and is easy to read. I’ve seen letters that Ben Clarke wrote, and trust me, each letter was signed by Ben “Clarke” and the handwriting is consistent. As stated every book that I have seen, including Custer and the Cheyenne, has misspelled his last name. Talk about an uphill fight to correct the spelling of a man’s name. Shameful.

A tip

My opinion of and respect for George Hyde and his interest and knowledge of the Indian wars is large. Grinnell could not have hired a better writer-editor. What I saw blew me away. If someone wants to write about the Grinnell-Hyde relationship and throw in George Bent, the mixed-blood Cheyenne who moved between the races and who worked with both Hyde and Grinnell, you might have one hell of a story to tell. A story that focuses on the three men during the time that they tried to document Cheyenne history, culture, and lifeway.

BTW, Grinnell did not limit his research to the Cheyennes. He also spent a lot of time meeting, befriending, and interviewing Pawnees that lived through the tumultuous times dating from at least 1830 and through the reservation years. There were other tribes that he also had an interest in (the Blackfeet, Sioux, Apaches to name three), but to what extent I currently don’t know.

“Success or Failure?”

I had announced this upcoming blog with the words: “Success or Failure?” Bad boy Kraft for there is no success or failure research—all is successful. Reason: If I find something, great! If I don’t, I now know that where I’m searching is a dead end.

If you are researching Cheyennes, do yourself favor and take a long-hard look at the George Bird Grinnell Papers.

The Man Who Walks With His Toes Pointed Out …

I used the word “Cheyenne” in the title of Custer and the Cheyenne as opposed to the proper word usage of “Cheyennes” as I’m not talking about a group of people but a single person. The title points to one person, a Cheyenne person.

This Upton and Sons, Publishers’ book cover is here as it makes this article publicity for the book (published in 1995 and still in print), which in turn makes the next image, which is from the book also publicity. You’ll see the importance of this below.

From 1849 until his death in 1876 he was the keeper of the Cheyenne Medicine (or Sacred) Arrows. As such, he was probably the most powerful person on the central and southern plains, and when he traveled to the north, there too. He had been a warrior, but now he was a chief, a mystic, and a man of peace. The arrows had been given to The People (the Tsistsistas, or as most of you know them, the Cheyennes), and they gave the Tsistsistas power over the hunt and their enemies in war. Ma?heo?o, their one God, their All Father, using the Tsistsistas’ profit Sweet Medicine, provided a set of rules for the arrows that must always be followed at all times. Otherwise a darkness would cover The People and tragedy would haunt them.

What I have just told you is an absolute key for the Sand Creek book working. And let me tell you this is no small task to pull off.

In three of my previous books the keeper of the arrows has played an important part. In the Custer book he is that lone Cheyenne of the title. You can bet that he’ll again play a role in Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway.

I had seen a lot of Mr. Reedstrom’s illustrations over the years and I contacted him about this and other images for Custer and the Cheyenne. He was gracious and allowed me to use the requested images, and in this instance he allowed me to change the title of his artwork. I will forever be grateful to him for in 1995 and continuing to this day I have zero photos of Stone Forehead. If you know of any, please contact me. (BTW, magazine and book publishers I designed this book along with over 250 books and countless newsletters and ad material over the years.)

He was known as Stone Forehead or Rock Forehead or the Man Who Walks With His Toes Pointed Out. He was also known as Hohonai´viuhk´tanuh, Nan-ne-sa-tah, Nan-ne-sat-tah, and by the white man Medicine Arrow or Medicine Arrows (and by the way, I have found yet another Tsistsistas’ name for him).

One online review ripped the Wynkoop book for specifically listing Stone Forehead’s various names. That was this reviewer’s major peeve: Why waste paper space listing crap that no one gives a shit about (there goes my “GP” rating; I’m back up to “R.”). I’ll tell you why … I’ll tell you why. Recently a book dealing with the Cheyennes talks about two different people: Stone Forehead and Rock Forehead. The author had no clue that he was writing about the same person. DUH????

I need not write any more about this, other than to say, “Hey, online reviewer sharpen your teeth, for my next Indian wars book will give you plenty to bitch about.” I can see his words now: “This tragedy of a writer refuses to learn. Instead of reducing the number of names for a stupid Indian, he has increased them. Un-f—ing believable!”

And the search goes on …

Liza and Manola pulled what I needed to see. They figured out ways to keep me working when they realized that I didn’t take lunch but simply sat at a table outside the Braun and continued to work. Actually on an online interview that is long overdue, is long-winded, and at the moment unsatisfactory. Worse, it isn’t close to being completed. At the moment I’m working at cutting and cutting and cutting. I owe a letter to Wild West, as well as an article on Geronimo, and let’s not forget the malpractice novel, Sand Creek, or everything that must be in place by September for a date with U.S. immigration (that might determine my continued residence in the U.S.).

lk spent prime time with Rick West at the two-day event without really knowing much of his background (dummy me didn’t know who he was other than he played a prime role the creation of the Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C.). I discovered an open, kind, and interested person. A good listener and someone I enjoyed getting to know, if only slightly. In case you don’t know, he is a full-blooded Southern Cheyenne peace chief. Also, in case you don’t know, he is president and CEO of the Autry National Center. I believe he assumed this position in December 2012. Earlier that year I had parted company with the technical world and didn’t want to approach him for fear that it might look like I was hustling him for a job. In 2011 I had approached him on a five-part documentary that would have been costly on Wynkoop and the Cheyennes. He wasn’t interested, even though I had key people lined up (including Indian wars historian Jerry Greene and Cheyenne Chief Gordon Yellowman; both spoke at the symposium).

Yes, I juggle projects. I must, for most projects take years to complete and no writer can disappear from the public for that long and expect his readers to return. That means articles must be written, talks (and this is now a sorry subject, and one from which I’ll not bend—when I go on the road I will receive my full salary and all expenses, as I had as recently as September 2012, or no talk). Look on the bright side; I have more time to write.

The days are busy, but on the plus side they keep me out of trouble.