Website & blogs © Louis Kraft 2013-2020

Contact Kraft at writerkraft@gmail.com or comment at the end of the blogs

Olivia de Havilland is a gorgeous, sexy, funny, bright, and very intelligent human being.

I know that this is true for I saw what I just said in person.

Trust me, the above by LK is a comin’.

Trust me, the above by LK is a comin’.

When Olivia turned 100 a lot of people sent me links that they found on the internet (I hadn’t searched for any—no reason required by me other than to say I dreaded reading them). This wonderful person and good actress and great hostess’s long anticipated birthday linked me up with Olivia Duke, who works in the entertainment industry and lives locally. She had posted an amazing amount of OdeH information on one of her social media sites, and luckily had seen a talk that I had delivered at the Burbank Historical Society (Calif.) a number of years back (Louis Kraft talk on Errol Flynn’s George Armstrong Custer), and contacted me.

One year later, 1941, Olivia played Elizabeth Bacon Custer in They Died with Their Boots On. I’m not alone when I say that both she and Flynn were brilliant as Mr. and Mrs. George Armstrong Custer. Their performances in this film were by far the best in the eight films they made together.

Others sent me links, such as friend Stan Maxwell. … A good friend of mine from the software industry, Sherry Weng, added a link that she had found on my Facebook page. There have been comments, which are always good, but alas the article posted on the internet that I’m about to comment on was/is loaded with errors and comments that are based—I’m certain—on a minimal amount of research (perhaps reading one or two or three articles without doing any real research). In the future I plan on dealing with this type of writing in both the Indian wars and the Golden Age of Cinema (and when that happens I will cite everything that I state). Actually the timing was good, as I needed a break from a very important blog (perhaps the most important that I ever write) that will be posted later this month.

You should read the link that Sherry shared with me (100 years of Olivia de Havilland handling sexism, her sister, and Scarlett O’Hara ) before continuing with this blog.

WARNING

If you like what you read in the posted article,

you won’t like what follows.

The link above is to an article that a fellow named Bob Mondello wrote. When I first read it I was appalled. I read it again and jotted notes. They follow.

First off I want to say that Mondello’s article is typical of what is often printed in magazines, newspapers, or online (and here I’m specifically focused on the Golden Age of Cinema, which includes Olivia de Havilland and Errol Flynn). Many of these articles are little more than mine fields of errors and inventive fiction. If you have any doubts with what follows, do your own research. If you do, you will see that what I say is true, and more important that I’m not attacking a fellow writer due to jealousy or for any reason other than pointing out falsifications due to a lack of research (as I don’t believe Mondello attempted to deceive the reading public). Regardless of what is touched upon below, Mondello’s article will continue to live on the internet and add to the continuous flow of misrepresentations of people and events.

From left: Hattie McDaniel, Olivia de Havilland, and Vivien Leigh in Gone with the Wind (1939). Olivia was nominated for her first Oscar: Hattie and Vivien won Oscars for their performances, and Olivia returned home that night empty-handed. (photo in Louis Kraft personal collection)

Mondello claims that Gone with the Wind is the most popular film of all time. I thought this was true at one time but no longer so. Recently a person I know proved to me that this is still true during a recent excursion to Lasky Mesa at the far-west side of the San Fernando Valley (Los Angeles, Calif.). We walked for miles up hills and down hills and over long stretches of flat land as he showed me some of the locations for Errol Flynn’s George Armstrong Custer’s Little Bighorn film locations where he died gallantly in They Died with Their Boots On (1941). From what I saw, temperature wise, it was supposed to be in the mid-80s that day. Ouch! It hovered just below the century mark. Thank God for lots of water. We also looked at some of the locations for the 1936 Flynn/de Havilland film, The Charge of the Light Brigade. On this day my guide found two locations he had been looking for from Gone with the Wind (1939) and Flynn’s great Adventures of Don Juan (1948). Other than pick up shots at the studio later that day this scene at the end of Don Juan was of Flynn’s and Alan Hale’s last scene together—ever!

LK on Lasky Mesa in the hills at the west end of the San Fernando Valley. I am standing in front of the area where Errol Flynn as George Armstrong Custer led the Seventh U.S. Cavalry to their deaths at the battle of the Little Bighorn in They Died with Their Boots On (1941). (photo © Louis Kraft 2016)

Back to Gone with the Wind: We’re talking about ticket sales here and not box office gross receipts. Recently Pailin and I saw The Legend of Tarzan (2016) at a first showing at an AMC theater. Price: $6.49/ticket. if we had gone at any other time: $19.49/ticket. Money totals, regardless of attempting to guess what .25 cent or .50 cent tickets might equal in today’s inflated pricing, means nothing. If you want to know what the most popular film was, count the sold tickets. (And actually here this is a corrupted figure, for Gone with the Wind wasn’t selling seats in many of the countries that now fork out millions of dollars to see American films.) … For the record I don’t like Gone with the Wind, but ticket sales speak for themselves, and when you realize that this film was released at the end of 1939, this is one amazing accomplishment.

LK enjoys Champagne with Olivia while we celebrated her birthday in her Paris garden on 3jul2009 and discussed her life and my writing projects. Although social, the entire day and evening was spent by me attempting to learn about this very special lady. (photo © Louis Kraft 2009)

The author states that OdeH (pardon me, but this is what I sometimes call her in my research and communication with other historians) was “apparently feeling that 49 films, two best actress Oscars, and a best-selling memoir were accomplishment enough for one career.” Mondello certainly doesn’t attribute this to de Havilland (and I know why, for this isn’t something that she would say). For example, Olivia has been working on an autobiography since before I came in contact with her (1996) and as far as I know she hasn’t completed the manuscript (I could say something here that is very relative but can’t for it will be in the introduction to Errol & Olivia, which will finally become my major book project after Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway is in production. That said, her autobiography is of major importance to her. (I know this for we have discussed it and she has queried me for information about her life more than once). BTW, I’m not privy to the reasons why Olivia has not completed her manuscript.

Back to Mondello: I believe that his quote (in the above paragraph) is similar to much that appears in printed biography. Reason: Biographers and would-be biographers all-too often throw out statements of “supposed” fact that in reality are little more than the author’s creation and opinion, and often this is in place to sell a premise that isn’t based upon fact.

Again quoting Mondelllo: “Friday in Paris, she celebrates her 100th birthday …” Without batting an eye I agree with this. In fact, she spent her birthday with her family and close friends.

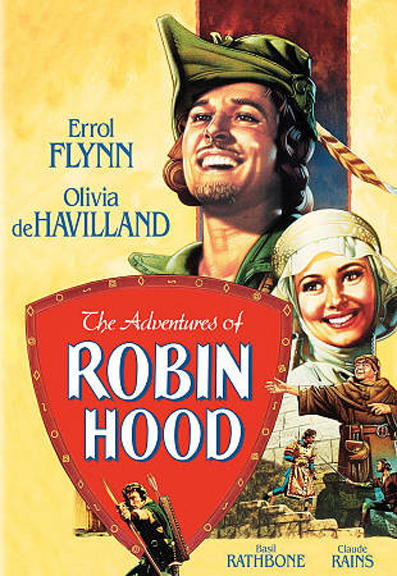

One sheet from the video release of the film decades ago. Mondello, for some reason, ignores Captain Blood and jumps to The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). I don’t have a clue why except that so-called Flynn experts have labeled this film the pinnacle of Flynn’s film career. I totally disagree, and it doesn’t even make my top 12 list of Flynn films. Certainly Olivia and Flynn were better in Four’s a Crowd (1938), Dodge City (1939), and They Died with Their Boots On (1941) in their films together. (poster in Louis Kraft personal collection)

Mondello then states: “She got her start on-screen as a sweet Hermia in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, graduated to being a sweet ingénue in a slew of forgettable comedies, and then someone had that bright idea of casting her opposite Errol Flynn. He was a swashbuckler, and standing opposite him, de Havilland got feisty.” I guess this ragged piece of baloney goes hand-in-hand with the adage: “If it is in print, it must be true.”

Ladies and gents, if you believe this, I have some beachfront property in Arizona that I’ll sell you at a cheap price. Trust me, for someday an earthquake will send California into the deep blue to live in legend with Davy Jones’ locker and many of you living on east side of what used to be the Colorado River will enjoy the occasional thrill of seeing a surfer or swimmer attacked by a Great White shark.

I need to reprint a portion of Mondello’s above quote: “… a slew of forgettable comedies” before she was cast with Flynn who “was a swashbuckler.” These two phrases totally discredit the entire article without reading it. Yes, they are that bad.

OdeH made two films after A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Alibi Ike (1935) with Joe E. Brown (which I have) and The Irish in Us (1935) with James Cagney and Pat O’Brien (which I’ve never seen). Two films, actually with big stars, and I certainly wouldn’t call them a “slew” of films. She was basically an unknown (or, if you will a starlet). Flynn, to date had two American films to his credit: 1) He played a corpse on film (with a total of less than a minute of screen time in The Case of the Curious Bride (1935), and 2) In Don’t Bet on Blondes (1935) he looked great in a little over five minutes of screen time in two scenes.

Was he a swashbuckler? Duh! I don’t think so.

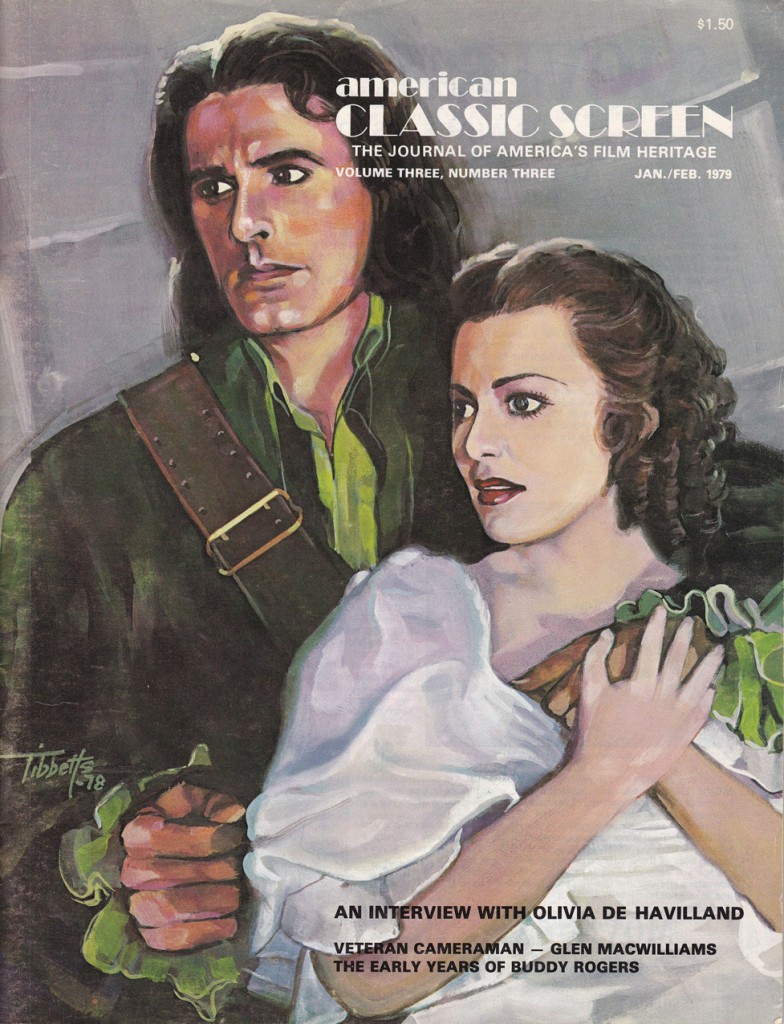

This is the January-February 1979 cover for a long-gone magazine that was decent. The art is nice, and I wouldn’t mind having the original. (magazine in Louis Kraft personal collection)

The Warner Bros. script for Captain Blood was based upon a portion of Rafael Sabatini’s great story of piracy about a doctor turned slave turned pirate, Captain Blood: The Odyssey (published 1922), hadn’t been cast yet, much less filmed. Heck Errol Flynn hadn’t held a sword yet. He was a swashbuckler? Give me a break.

Warner Bros. wanted the British star, Robert Donat, to play Blood, after his recent film hit, The Count of Monte Cristo (1934), and Donat’s only film shot in Hollywood. It wasn’t to be as Donat turned down the role and returned to England. This began a frenzy of casting as Warner Bros. frantically looked for their Peter Blood and Arabella Bishop. There were many screen tests and one by one major stars and smaller players were eliminated. Two, who looked great together in their tests remained in the running, but both had no marquee value for a major film. For the record Flynn made it clear that Jack Warner dared to gamble on him (and Warner confirmed this). Flynn and de Havilland landed the roles. When Captain Blood premiered in New York City in December 1935, over night Flynn became a superstar (BTW, the word/term didn’t exist then) and de Havilland became a star.

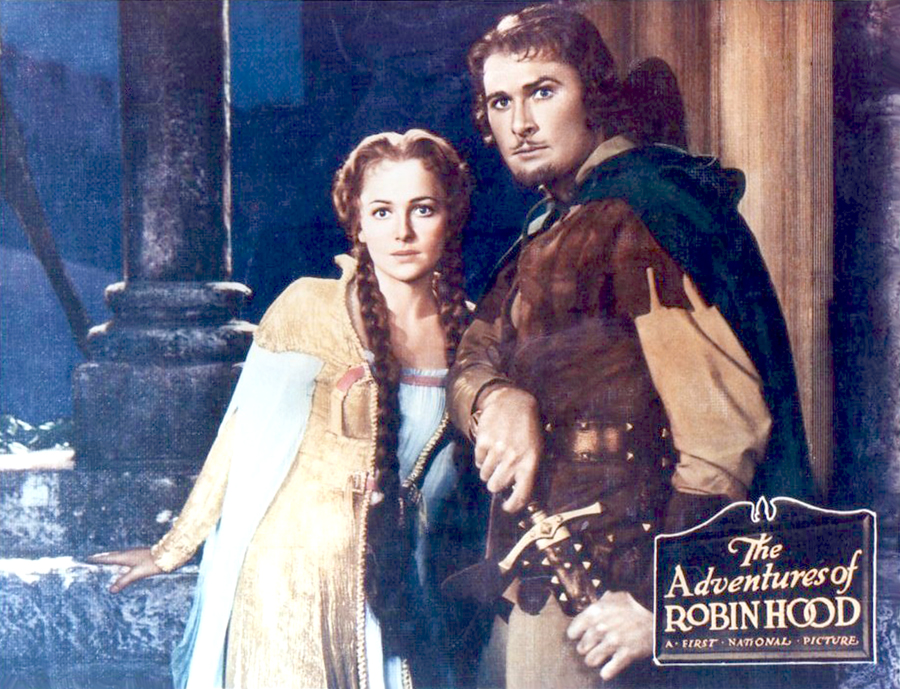

A lobby card from the 1938 release of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Mondello follows the above with stating that The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) made Olivia a star. Hello! As stated above the major hit, Captain Blood, made her a star, and the follow-up hit with Flynn, The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936) reconfirmed that she was a star. And what about the three historical films that she did without Flynn before The Adventures of Robin Hood. They didn’t count?

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. sits with Vivien Leigh, and Olivia during the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awards ceremony in 1940. Although Olivia didn’t receive her first Oscar on that night she seemed to be enjoying herself (although she later admitted that losing to Hattie McDaniel hurt). (photo in Louis Kraft personal collection)

From here, Mondello’s fictions grow, just like Pinocchio’s nose. “Happily, a rival studio asked if it could borrow her as a foil for its ditz—Vivien Leigh, who had just been cast as vain, self-centered Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind. …” Huh? This is one of the biggest pieces of BS posted in our modern era of print in regards to this great film based on Margaret Mitchell’s massive best-selling book of the same name, and fans continue to buy into the various fictitious versions of this hook, line, and sinker.

If you didn’t know it, while producer David O. Selznick searched for his Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler Warner Bros. offered the package of Bette Davis and Errol Flynn. This offer, which included both stars and not just one of them, was refused. For me to address Olivia’s fight to land the role of Melanie Hamilton would cost at least 5,000 words (I deal with this in Errol & Olivia), but the bottom line is that Jack Warner refused to allow de Havilland to try out for the part of Melanie. When she landed the role behind Jack Warner’s back, believe me that a lot a SSSS hit the fan. Warner eventually relented and allowed de Havilland to play the role, and he received James Stewart in return.

Original art by Susan M. Goulet of Olivia de Havilland as Lady Penelope Gray in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex in LK’s personal collection. When I presented Olivia a print of the art at her home in Paris she knew exactly who she portrayed in the image. BTW, a few years back I posted this art in a blog about Ms. de Havilland and offered a (two + hours) “swashbuckling” lesson. Two ladies correctly named who Olivia played in the image but both didn’t live near California and weren’t able to claim their awards. Here, swashbuckling is a term sometimes used for stage (and film) combat. Original art in Louis Kraft personal collection.

Next Mondello asserts that “Off-screen, though, de Havilland was now able to be more assertive.” Huh? In 1939 de Havilland would be relegated to a minor player in the Flynn/Bette Davis film, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, which was nominated for five Oscars. For the record, de Havilland, who had major tantrums on the set, was very good in her ten or 15 minutes in the film (a part that did exist in Maxwell Anderson’s major Broadway hit but was expanded for the film, Elizabeth the Queen, 1930). … And from my point of view she was the best thing in the film. Like her performance in Dodge City (1939), and also with Flynn, she used her anger to improve her performance.

As far as the suspensions go, OdeH had been placed on suspension often, but it wasn’t “on a six-month-suspension.” Her suspensions were for when she refused to play a specific role, and the suspension was for the time-period that the character she refused to play would have been on call to perform the part. Two months per film? Three months per film? No, for her roles usually required much less time to complete. Why? Using Flynn for an example: Most often he filmed on almost every day. Let’s say a three-month film schedule. Conversely, OdeH, in one of Flynn’s films, might only work 20 days (or less), which means that her suspension was related to the number of days that she missed when she could have, or should have, worked.

LK presenting Olivia de Havilland to former girlfriend Diane Moon on the night that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honored her in June 2006. They hit it off, and she would travel to Paris with me three years later to again spend time with Livvie (as Errol Flynn and others affectionately called Olivia). (photo in Louis Kraft personal collection)

OdeH’s suspension time was supposedly a combination of all the roles in which she refused to perform, and is the time that Warner Bros. claimed that she still owned them to complete her seven-year contract. Personally I don’t understand the math here, for upon refusing to perform in a film WB immediately placed her on suspension.

Olivia de Havilland disagreed with Warner Bros. and argued in court that her contract was based upon linear years. WB stood firm—she owed them for all the remaining time that she didn’t work. At this time Warner Bros. circulated a letter that demanded that de Havilland not work in film or on stage in the United States—they blacklisted her. When the case finally went to court in the mid-1940s de Havilland won, and gained her freedom. Every actor that makes millions of dollars today owes her and her courage a hearty thank you.

Photo of Olivia de Havilland when she arrived at the shindig that the Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences hosted in her honor in June 2006. (photo © Louis Kraft 2009)

Free from Warner Bros. de Havilland began to freelance, and yes she did hit the heights of her film career. At this time Mondello proclaims that “But by Hollywood standards, she was now an old lady of 33 [meaning in 1949]. Roles came less frequently back then to actresses as they approached their 40s …” The age of 33 is approaching 40 and is old? To Each His Own (1946), the title of the first of Olivia’s major films after she escaped being an indentured slave at Warner Bros., easily places this absurd statement in context—she was thirty at the time. Of course this film had nothing to do with her winning her freedom, but it definitely dealt with her still being a young woman playing an older woman.

Unfortunately the writer of the article ignored the personal changes in de Havilland in the mid-1940s and then the major changes in her life during the 1950s. Mainly, what had changed and was important in her life. Yes, she turned her back on Hollywood, but it was for a life that she then craved—a life with her (in this case) second family in France (which included her son from her first marriage). Film work did continue, but it was when she wanted it, and more often than not it was in Europe.

A Spanish mini-poster of They Died with Their Boots On (1941), one of LK’s favorite films of all time. (poster in Louis Kraft personal collection)

I know that everything that Mondello said about OdeH and sister Joan (Fontaine) is pure hokum (read that this writer had no clue of what he was writing about when he wrote the article). I know some of what I’m talking about here first hand, and it ain’t for the internet. Let me just say that I keep promises. Without a doubt the anger that has been publicized between Olivia and Joan was real. Actually, other than one major incident in the early 1940s and then something else many years later, OdeH refused to discuss her sister with me. One time when I asked about Joan’s autobiography, A Bed of Roses, Olivia dismissed it as little more than lies. Every side has their point of view. I’ve heard Olivia’s but unfortunately not Joan’s other than in her autobiography. I’m certain the that truth lies somewhere between the two sisters who both enjoyed unbelievable success as actresses.

I think that the above covers what I have to say about Mondello’s less than sparkling article. … I hope that when Errol & Olivia is published that it will clear up once and for all time some of the blatant errors and misstatements in the above article, many other articles, and a handful of books that should have never been published.